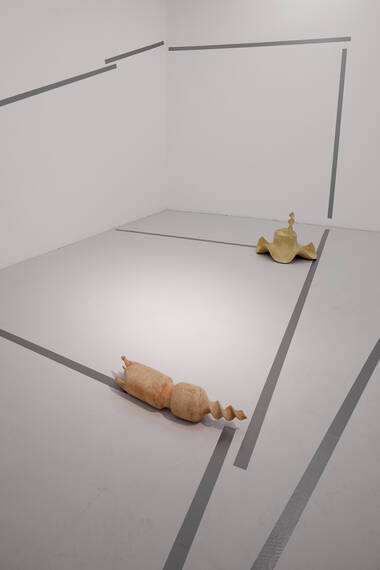

Spring and All

10. 3. – 28. 5. 2023

opening: 9. 3. 2023 from 6 pm

artists: Darina Alster, Veronika Šrek Bromová,

Mira Gáberová, Anna Hulačová, Petra Janda, Karel Kunc, Václav Litvan

Darina Alster´s performance will take place

during the exhibition.

curator: Mariana Serranová

visual and architectural design: Jan Fabián

I. Spring and All

By the road to the contagious hospital

under the surge of the blue

mottled clouds driven from the

northeast-a cold wind. Beyond, the

waste of broad, muddy fields

brown with dried weeds, standing and fallen

(…)

William Carlos Williams, Spring and All (1923) [1]

I would like to point out in advance that Spring and All is not an exhibition about spring, but rather about everything possible, including spring. The title of the exhibition is taken from a poetry collection by William Carlos Williams, in which the author, a doctor by profession, describes the bleak pre-spring landscape after a trip to a hospital riddled with infection after the First World War. One hundred years on and the mood in the lead up to this spring is by no means dissimilar. The period of the pandemic has spilled over into political mayhem of frightening proportions. And all of this is taking place against the backdrop of a worsening environmental crisis. Though according to all the assumptions of the astronomical year we may be entering the spring phase, it is impossible to ignore the escalating war and its destructive effects. One way or another there will be spring and hopefully soon peace.

A faithful translation of a poetic text is sometimes almost impossible. Within the context of the exhibition cycle Seasons [2] in our geographical zone, apart from the relatively apposite Spring and All, perhaps Spring and so on emerges as an interpretation close to our lived experience of cyclical time. Spring could certainly be simply spring, without any additional attributes or loans. However, a suitable metaphor is being sought in the knowledge that it is the seasons – the weather and its fluctuations, or perhaps even its irreversible transformation – that are significantly inscribed in the development of events and the collective atmosphere. The cycle Seasons is a shared meditation on time in its various dimensions. It is perhaps also a search for reliable coordinates and certainties in times of uncertainty. When there is chaos and devastation on earth, a more universal principle is sought that cannot be shattered. But if the natural cycles as we know them are shattered, what is left?

Alienation from nature has been experienced by modern humankind in our latitudes with full consciousness for several generations. We live with the distressing feeling that we are ignoring something of crucial importance, that we are lending our support to a society that disregards sustainability and the possibility of survival for future generations of all living species. Contemporary developments are also making us aware of other shifts through the unpredictable course of the seasons. The current state of affairs is often presented as a turning point, a loss of control. Yet years do not play a role: from a global perspective the future of life on earth is measured symbolically in all the small units of time that remain until the inevitable catastrophe is averted or at least mitigated.

II. Spring

Proto-Slavic *jaro, from Proto-Indo-European *yóh₁r̥ (“year, spring”). Cognate with English year, German Jahr (“year”), Latin hōra (“hour, time, season”), Ancient Greek ὥρα (hṓra, “year, season”). [3]

Do you think I don´t know about power? You think I was born green?

I was.

Mess up my climate, I’ll fuck with your lives. Your lives are a nothing to me. I’ll yank daffodils out of the ground in December. I’ll block up your front door in April with snow and blow down that tree so it cracks your roof open. I’ll carpet your house with the river.

But I’ll be the reason your own sap’s reviving. I’ll mainline the light to your veins.

Ali Smith, Spring (2019) [4]

The exhibition Spring and All is also about waiting for spring. Some of the works on display were created in the prevernal season, during the search for the ephemeral favourite amongst the seasons. Somewhat disturbing are the proliferating warnings that spring and autumn are no longer taking place in the wake of climate change, and that we will be left with only summer and winter. But let us not give up hope. In phenology, the study of natural phenomena that recur periodically, the term “season creep” is now used to describe the phenomenon of unusually timed temperature changes, such as an early spring. These shifts cause great problems not only to scientists and gardeners, but also to migratory birds and flowering plants.

Reconciling ourselves with a weakened nature today, when we can fear extremes and anomalies from spring to winter, holds up a mirror to our own destructiveness. We have no choice but to monitor further developments with sensitivity and care. In an era of political extremes and social uncertainty, when the disrupted natural order no longer provides the necessary and reliable coordinates, what is there to fall back on?

In the novels of Scottish author Ali Smith, the concept of time is a way of expressing the characters’ sense of alienation and separation. Time is somehow distorted; the surrounding events, civilisation’s ailments, a feeling of unease with the devaluation of values and the limits of our knowledge of reality all enter into our personal narratives, altering their course. Leaving aside the author’s many political allusions and motivations, her quartet of novels is not a picture of the episodic existential crisis of her protagonists, but also of the transience of life. She wrote of time in its cyclicity simultaneously with political events taking place in Great Britain, Europe and the USA. Autumn (2016), Winter (2017), Spring (2019) and Summer (2020).

Certain parallels in the dynamic relationship between figure and context can be found in contemporary figurative art. It would appear that, the more complex reality becomes, the more the human figure seems to be removed from its environment. Or in other words, it is precisely because it is elusive and ambiguous that it is part of an environment that is difficult to define. Its relationships with its surroundings are complicated, its sojourns transient, its moods and opinions are subject to numerous twists and turns. Our own activities, alien to nature, have an impact on our relationship to our own corporeality and identity.

III. and All

Embrace diversity.

Unite—

Or be divided,

robbed,

ruled,

killed

By those who see you as prey.

Embrace diversity

Or be destroyed.

Octavia E. Butler, Parable of the Sower (1993) [5]

There was a strange stillness. The birds, for example—where had they gone? Many people spoke of them, puzzled and disturbed. The feeding stations in the backyards were deserted. The few birds seen anywhere were moribund; they trembled violently and could not fly. It was a spring without voices. On the mornings that had once throbbed with the dawn chorus of robins, catbirds, doves, jays, wrens, and scores of other bird voices there was now no sound; only silence lay over the fields and woods and marsh.

Rachel Carson, A Fable for Tomorrow, Silent Spring (1962) [6]

In her dystopian novel Parable of the Sower (1993), Octavia E. Butler drew on the form of the journal. We follow chronological developments over a period of several years. In the journal entries, the teenage heroine describes the bleak future after climate change in California. She conjures up an era of drought, fires, human and animal suffering, aggression and looting. The first entry is from July 2024, and over the course of the following years we see the narrator develop. The mantra that she repeats throughout the story embodies a deep desire for a return to a balance between people and land. The narrator’s entire plot and thought processes take place in an arid landscape with inaccessible water, the details of which take pages to describe, while the rare joy of spring rain can be encapsulated in a single paragraph. In their daily survival, people lack goals and fall into irrational and destructive behaviour.

The all are not people, but species becoming extinct. Moreover, it is not just future generations of people, but future generations of all animal and plant species and other living microorganisms. Like other writers of dystopian fiction, Octavia Butler was influenced not only by her observations of the disrupted balance in the environment, but also by the warning voices of climatologists and scientists calling for change, for the preservation of diversity and natural resources. An emblematic example is Rachel Carson, who was one of the pioneers of ecological thinking about poisons, focusing on the effects of pesticides on the health of landscapes, people, animals and plants. Her book still makes for uncomfortable reading and many attempts have been made to discredit it. The message of her balladic A Fable for Tomorrow, which opens the science-based arguments of Silent Spring, is crystal clear. It is incredible that we have been waiting 60 years for change and live with the knowledge that pesticides are still part of global agriculture.

The year is 2023, the record temperatures in our temperate zone are epochal. The extent of the forests that burned last summer is astonishing. It is unlikely that next year will not see both hemispheres burning once more. Nevertheless, it is still striking that thirty years after Octavia Butler’s ruthlessly rendered fiction was published, our current situation may not be so far removed from her catastrophic vision of a distressingly near future. The planet’s volatile cycles reinforced mixed feelings that we cannot ignore. However, the earth continues to turn from spring to winter, and we with it. Daylight and the darkness of night continue to shape our vision.

Marinana Serranová

(transl. Phil Jones)

[1] William Carlos Williams, Spring and All (New Directions Pearls), New York, 2011, pp. 11–12.

[2] The timetabling of the four exhibitions in the Cursor Gallery during 2023 aims to follow the time defined by one year. In a time of climate change, we view the risks created by meteorological fluctuations, the annual advance of global warming and the increasing likelihood of natural disasters with unprecedented concern. The seasons, organised into quarters, by their very physical nature ultimately influence our activities, planning, time management and our sociability.

[3] en.wiktionary.org/wiki/jaro

[4] Ali Smith, Spring, Penguin Books, p. 8.

[5] Octavia E. Butler, Parable of the Sower (1993)

[6] Rachel Carson, Silent Spring, Penguin Books, 2000, p. 22.

A New Beginning

After a month-long hiatus, the exhibition has undergone a change. With the arrival of Easter, Petra Janda’s straw Marena and the installation evoking a ceiling by Jan Fabián have departed. The reason is not spring as such, nor the drop in rainfall and the already receding cold, but problematic material containing toxic asbestos. With the agreement of the exhibitors and the Cursor Gallery, this sensitive conflict between a natural porous object and inappropriately recycled industrial panels has been removed. An audio installation by Darina Alster entitled Earthseed has joined the exhibition, which expresses the vertical dimension of the human being that makes it possible to overcome adversity and create a new unity. The work is based on Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower, which, incidentally, is the leitmotif of this year’s series. Earthseed represents both a symbolic reconciliation and the opening of a new chapter.

Is not the current political situation a clash of old and new social structures? Is it not also a sign of the need for change in the sense of sustainability? The facts of the essence of the material world are measurable, testable, objective. Their symbolic quality, on the other hand, is shared through complex cultural contexts and traditions. A decisive, radical break with continuity and the past is the subject of utopian visions, the lifetime of old materials has its limits, just as the present is an intergenerational dialogue.

The reopening of Spring and All after talks with the exhibitors and the gallery has contributed to a more rigorous focus on the interconnectedness between the organic and the inorganic, technology and the natural world. In art we pursue a deeper reflection on the relationship between natural and human production, the different tendencies in thought and in their material realisation. For example, compostable straw and durable concrete represent completely different directions from the perspective of sustainability. Recyclability is another example of such a change.

In nature, spring is the beginning of a new cycle, and its real celebration in a cultural sense is Easter. Pagan rituals are linked with the burning of the Grim Reaper, while the Christian tradition links the Passion and the Resurrection, creating a symbolic parallel to vegetative growth. Was this a coincidence, or does everything that happened drive our desire for ethical and sustainable practice in the arts and other sectors? Indeed, Easter is a time that symbolically traces the spiritual dimensions of death and rebirth. Within the context of our spring exhibition, then, it is another invitation to seek dialogue between the unhealed conflict of past and future.

Mariana Serranová

The program of the Cursor Gallery is possible through kind support of Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic, Prague City Council, State Fund of Culture of the Czech Republic, City District Prague 7,

GESTOR – The Union for the Protection of Authorship

Partners: Kostka stav

Media partners: ArtMap, jlbjlt.net and artalk.cz

Vyjádření k znovuotevření výstavy Spring and All