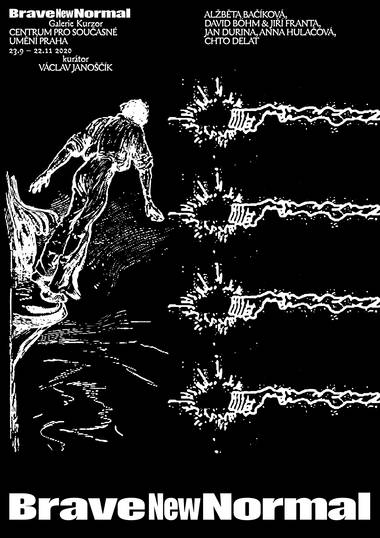

Brave New Normal

23. 9. – 22. 11. 2020

opening: 22. 9. 2020 from 6PM

artists: Alžběta Bačíková, David Böhm and Jiří Franta,

Jan Durina, Anna Hulačová, Chto Delat

installation in the courtyard area: Michal Čeloud Šembera

curator: Václav Janoščík

Download the exhibition brochure here

Chapter 1

Good things don’t change

MacGyver: “It was bound to happen. Things change.”

Pete Thornton: “Not always. Good things don't. Don't you ever change, MacGyver.”

MacGyver, The Stringer (1995)

It all seemed to be going so well. We emerged from the wrong side of history and set off on the path to the consumerist dream of liberal democracy and capitalism. We lived through transformation, reported solid growth, and enthusiastically adopted the role of younger sibling closing the gap on the West. And so over the last thirty years we have focused not only on GDP and supermarkets, but also on pop-culture and new heroes.

The excessively muscled action heroes of the 1980s (Sylvester Stallone, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Jean-Claude van Damme, as well as Richard Dean Anderson in the role of MacGyver) were swept away by the new Star Wars trilogy (1999, 2002, 2005). While traditional agents of the democratic world often found themselves up against political opponents (the Cold War, dictators, organised crime, even battles with extraterrestrials), the Jedi Knights abstracted their heroism into a mythological battle between good and evil.

In their wake came comic-book superheroes, whose classic form in the 21st century was in the Dark Knight trilogy directed by Christopher Nolan (2005, 2008, 2012). But the accumulation of series and universes was not enough and a whole army of superheroes entered the scene. The Avengers series (2012, 2015, 2018, 2019) from Marvel defined this multi-hero genre and defeated the competing universe of DC Comics.

Superhero narratives have successfully incorporated the experience of the internet, the more intense participation of fans, and several political problems, such as the mass arrival of female heroines and identity politics in general. The traditional battle between good and evil has become more complicated (Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice, 2016), though it remained at the heart of these narratives, which continue to outgross other films.[1]

Chapter 2

Heroes of the crisis

“I hope we get it back. And something like a normal version of the planet has been restored. If there ever was such a thing. God, what a world. Universe, now.”

Tony Stark, Avengers: Endgame (2019))

But things are changing. This year has seen not only the covid-19 pandemic, but also escalating political problems (from Hong Kong to Belarus to BLM) and increasingly pessimistic forecasts of the impacts of climate change. The seemingly inviolable world of superheroes is also reacting. The seriousness of the crisis keeps intensifying.

Not even Avengers: Endgame, in many respects the final and definitive superhero film and the culmination of a certain era, offers the traditional happy end. After the final battle it is more about dealing with loss, acknowledging the victims, and nurturing qualities such as resilience, robustness and an ability to respond to crisis. It is this last value that forms such a crucial social axis today.

It is not simply the ubiquitous economic pressure, the return of nationalist not to say xenophobic sentiments, the multiplication of geopolitical problems, the media presence of crises around the world and, of course, the never-ending series of interlinked environmental problems, but also the far more personal need to be constantly involved in the work process, whether due to financial necessity or career requirements, the pressure on our integrity, awareness and ability to be oriented in complex issues from American identity politics to pandemiological strategies. It is as if we ourselves are to be action heroes, who tolerate constant pressure and exhaustion with the calm of a Zen monk and the confidence of Iron Man.

And so the heroic narrative has shifted from the classic model, involving the anointing and training of the main and ultimately invincible character, to a focus on his or her ability to deal with loss, failure or self-sacrifice. While the traditional model was defined by the onset of crisis, the reaction thereto, and the vanquishing thereof, Avengers: Endgame and many other films no longer hold out the hope of the restoration of a calm and ordered world, but insist instead on the ability to withstand ongoing crisis or to return nostalgically to an idealised past. Captain America (2011), Wonder Woman (2017) and Captain Marvel (2019) are not only set within key heroic junctures of American history, but subliminally highlight the dividing line between a past characterised by clearly defined identities and classic heroism, and the entanglement of the present.

Chapter 3

Becoming oneself

“Then Prometheus, in his perplexity as to what preservation he could devise for man, stole from Hephaestus and Athena wisdom in the arts together with fire—since by no means without fire could it be acquired or helpfully used by any — and he handed it there and then as a gift to man.”

Plato, Protagoras (321d)

The task of heroic stories ranging from the myths of yore via fairytale princes to Spiderman is, of course, to drive our ability to identify ourselves, to examine not only the figures themselves, but the properties and values which they stand for. If we take this to its extreme, we are never ourselves, we are always surrounded by many other, more ideal versions of ourselves, a plurality of goals, aspirations, as well as disappointments and fears. We are constantly torn between what we are and what we want to be. Or rather, inasmuch as our dreams, visions and heroes are not simply a consumer backdrop but have the ability to genuinely change our lives.

Twentieth-century philosophy worked in this direction. It abandons the idea of a simple ego, a definitive identity, a Cartesian subject. It reveals the complex currents and process by which we ourselves are formed that never end. A series of French thinkers – Gilbert Simondon, Gilles Deleuze, Bernard Stiegler – are no longer concerned with being, but with becoming someone, not identity as a state, but individuation as an open process.

For Stiegler, for instance, individuation is above all threefold – psychological, collective and technical. Of course I develop internally as a personality, but this cannot be separated from my becoming a part of larger wholes. This means that creating “I” cannot be separated from creating “We”. However, my identity is also shaped technically, in the broadest sense of the word.

I do not develop simply through direct contact with others and my internal life. My conduct is structured by external principles, e.g. the quotidian rhythm or working hours. I also draw on repositories of cultural content and stories such as films or the internet. These are all external, i.e. the technical conditions of my life, whose role in contemporary society has exploded in such a way as to overwhelm me with many possibilities, as well as burdens and bullshit.

It is in this direction that we can understand one of the first heroic narratives of our culture, the myth of Prometheus. Unlike other animals, which have claws, fur, strength, speed, and other abilities with which to ensure their survival, human beings have remained naked. Prometheus steals fire and creative power or craft [techné]. The human being is an imperfect being. Something is always missing. We have to wrestle with the outside world and refashion it. It is here that the meaning resides not only of heroism but also technology.

Chapter 4

Pharmacology of the present

“Are you having any negative thoughts?”

“All I have are negative thoughts.”

Joker (2019)

Bernard Stiegler is not content to remain amongst the heroes of antiquity. He is perhaps the most important thinker devoted to the present. He speaks without discomfort of today’s world as a human catastrophe that does not reside only in the power of technology over man or in ecological apocalypse. The core of this catastrophe is in our inability to create the I/We relationship, i.e. to participate in psychological, collective and technical individuation.

The dictates of consumerism and indifference, information overload, the dominion of stupidity and the inability of universities to take responsibility for the production of proportionate knowledge and thus collective individuation – all these are problems that are not simply somewhere out there, but threaten the ability of all of us to be ourselves.

At the same time, Stiegler rejects a simple imposition of resistance (to technology or social media, for instance). He offers a programme of pharmacology (from the Greek pharmakon, meaning both cure and poison). He focuses on the delicate relationship between man and technology. Pharmacology combines in itself the capitalist reduction of desire to consumption served by a technical system of marketing or networks, with the fixation or love [cathexis] that offers us a radically personal yet collectively shared expression as individual and free beings.

We must work through (Durcharbeitung, Sigmund Freud) our problems and not sheathe them in the flawlessly smooth, synthetically realistic surface of Hollywood films. Last year’s Joker (2019), which represented the culmination of the era of superheroes in an even darker way than Avengers: Endgame, took a step in this direction. Anxiety, depression, unemployment and hopelessness are pharmacologically squeezed beneath the mask of a clown. Laughter becomes paroxysmal and the hero gradually grows into a mask that can no longer be removed. It is as though it is no longer possible to play at being anything these days, because sooner or later we will become that which we are pretending to be.

Jan Durina works in a similar way with mask and costume. His work with textiles and his own identity is not therapeutic, but pharmacological. It inverts the interior and exterior, presentation and introspection. By concealing itself, it remains open.

Chapter 5

Heroes of work

“That man is best who sees the truth himself.”

Hesiod, Works and Days

We see now that heroism is at least twofold. On the one hand, excessive, active, effective, possibly even toxic and Odyssean; on the other, slower, more collective, pharmacological and Promethean, associated with the victim but above all with work. The first instance is based on the sovereignty and invincibility of the hero, while the second draws on an awareness of his or her own inadequacy and the need to take care of themselves and others.

Both concepts of ethical behaviour and a heroic life have been intertwined since antiquity. As well as Achilles, Hector and the Homeric epics, we also have Hesiod’s didactic poem Works and Days. In this work heroism is not about struggle and fame, but about day-to-day work, not about the heroically punctual presence of the “moment of truth”, but the cyclical and future-oriented periodicity of land cultivation and looking out for others as they look out for you.

It is perhaps unnecessary to add just how much we need this type of heroism, with its slow tempo, constancy and sensitivity in an era of planetary change and conflict. It is worth reminding ourselves how complex is our relationship to the heroisation of labour in Central Europe, where it is associated with the communist past. In the Czech Republic especially one must forget the historical hysteria towards the totalitarian regime and a certain folkloric anticommunism that simply regurgitates empty slogans, does battle against illusory threats and covers up problems a thousand times closer.

A return to work in a similar sense informs the work of Anna Hulačová, whose sculptures resemble a factory environment, productivism or workerism, but explore more deeply the touch, interface, connection and pharmacology of work. Faces, machines and hands open without stiffening and remaining something functional. A machine is not simply controlled by humans, nor is the worker subordinate to technology. Instead they pulsate with mutual activity.

Alžběta Bačíková’s projection then draws the problematic of work and the perspective of the everyday even more in the direction of the heroes themselves. The heroine and hero here is not simply the warrior, feminist and writer Qiu Jin (1875–1907), but also Eda, immersed in kung-fu and Chinese culture, as well as in writing short stories. This is not a simple narrative. The artist gets to know the narrator as well as the narrator knows his heroine. The speech and gaze of the camera are again pharmacological. They do not describe, but describe an identity, they intersect reality by means of quick-fire editing and new connections like the blows of martial arts.

Chapter 6

The freedom to suffer

Sam Porter Bridges: “No, America's finished.”

Amelie: “Sam, if we don't all come together again humanity will not survive.”

Sam Porter Bridges: “We don't need a country, not anymore.”

Death Stranding (2020)

Bernard Stiegler became interested in philosophy in prison, where he served a sentence (1978–83) for armed bank robbery. He writes in his memoirs that it was an impulsive act interrupted by the impossibility of action, the absence of the world, and that it was his experience of prison that led him to philosophy.[2] Thinking, therefore, that is not simply intuitive, but serves to undermine action, requires time, a Möbius strip in deliberation, possibilities and otherness. At the same time it develops its own heroism. Heroism is constantly different, it is to be confronted with the exterior and to reject enclosure. It is to desire this otherness and exterior while shunning the dictates of uniformity, stereotype and consumption.

When, now, we turn to heroes, perhaps it is not because they bring us a Brave New World, but in order that they be partners in the discussion of the values and character of our societies, so that in relation to them we can become better, so that they become part of a new world that will not hide behind an idealised past, but will face up to the real challenges of today. I see this relationship to values, goals and visions as the new normality in the best sense of the word.

I perceive similar attempts being made by Jiří Franta and David Böhm, who do not use drawing in order to represent or simply depict the world around them, but actively enter said world with rapid gestures as well as with demanding, drawn-out work, the repetition of shapes, and the re-designation of symbols. Above all their drawings are never finished, but escape within the processes of repetition, transcription and individuation.

Perhaps this all sounds simple. But these reflections on heroism and on what it means to act meaningfully, this heroism in thinking, always arises from some dark depth that I cannot describe in simple terms. Everyone has to experience it in person. Stiegler himself, with his intimate knowledge of imprisonment, claims that freedom involves suffering.[3] Inasmuch as “being oneself” is not simply obeying the nostrums of the agony column of a lifestyle magazine, but a serious task, then it must lead not through liberation, but through a profound alienation. I am an independent being precisely because I do not fit in. I am radically other and yet I cannot live without sharing my otherness. And my ability to act often disarms me.

The work of the group Chto Delat, above all their two-channel video dedicated to “safe havens”, focuses on these pharmacological places of care, solidarity and otherness, as well as shelters. In these utopian spaces, art is something independent of the “art world”, something more generally human. However, in addition to the need for this inclusive approach to art, we have to acknowledge that we also need exclusive spaces of shelter and privacy. Inasmuch as my internal life yields itself to the outside only indirectly through the play of surfaces (whether these comprise art or my clothes), it is the basic interface of our freedom and perhaps our heroism.

Bernard Stiegler died on 6 August, just as I was beginning preparations of this exhibition. He will always be my superhero.

[1] In 2018 the top ten grossing films at the box office featured six superhero films, and five in 2019. In addition, Avengers: Endgame, which earned almost $3 bn, became the top box office movie of all time (leaving aside inflation).

[2] Bernard STIEGLER, How I became a Philosopher. In: Bernard STIEGLER, Acting Out, Stanford: Stanford University Press 2009, 1–36.

[3] Ibid., 19.

The programme of the Center for Contemporary Arts Prague receives support from the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic, Prague City Council, State Fund of Culture of the Czech Republic, City District

Prague 7

partners: Kostka stav

media support: ArtMap, jlbjlt.net and UMA: You Make Art