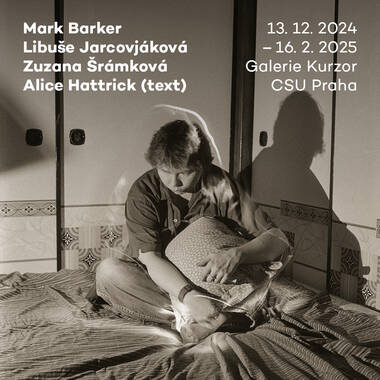

Mark Barker, Libuše Jarcovjáková,

Zuzana Šrámková

with text by Alice Hattrick

13. 12. 2024 – 16. 2. 2025

opening: 12. 12. 2024 at 6 pm

curator: Zuzana Blochová

collaboration: Marek Meduna

exhibition display: David Fesl

graphics: Jan Šerých

The exhibition focuses on the physical experience that artworks can capture and subsequently evoke. Through observation of themselves and others and the documentary approaches of photography, sculpture and drawing, the artists depict internal processes, loneliness in the body, and the intertwining of individual and social bodies.

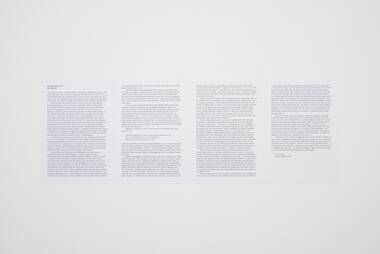

The exhibition, which remains nameless, presents and joins the work of one visual artist and two documentary photographers that engage with the aforementioned themes from various positions and to varying degrees. Writer Alice Hattrick, whose 2021 book Ill Feelings is a “personal and political reckoning with the nature of illness, inheritance, time, silence, bodies and invisibility” (Francesca Wade), was invited to write a free-form text related to the exhibition and the work of the exhibiting artists.

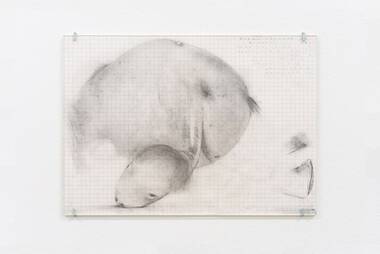

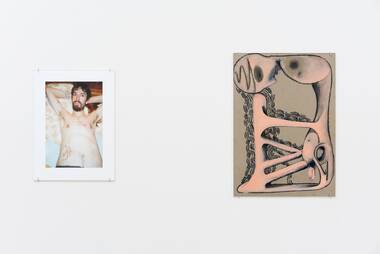

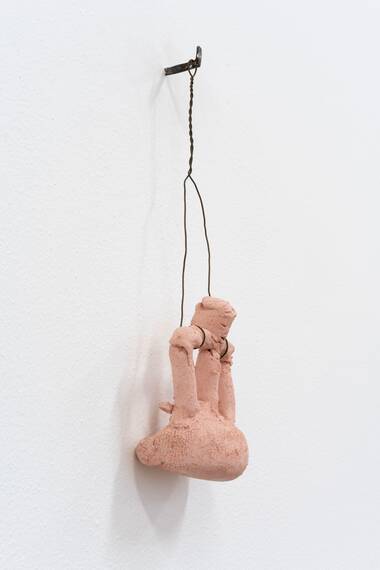

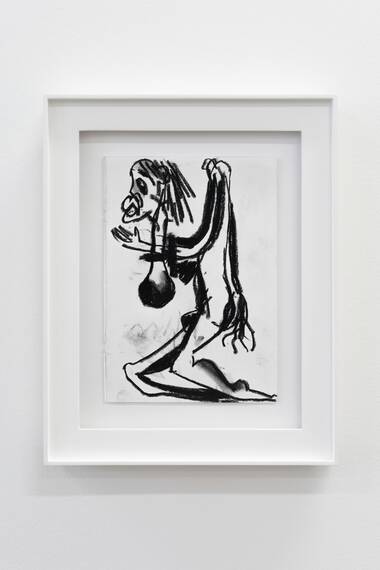

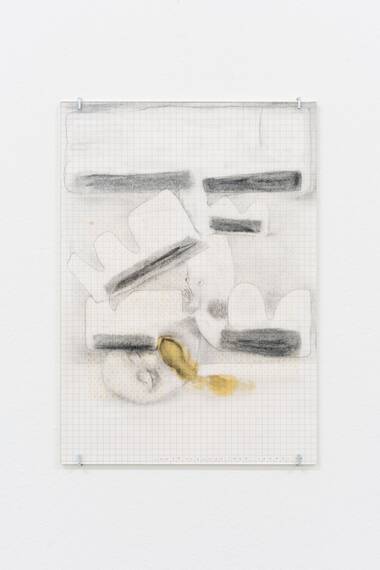

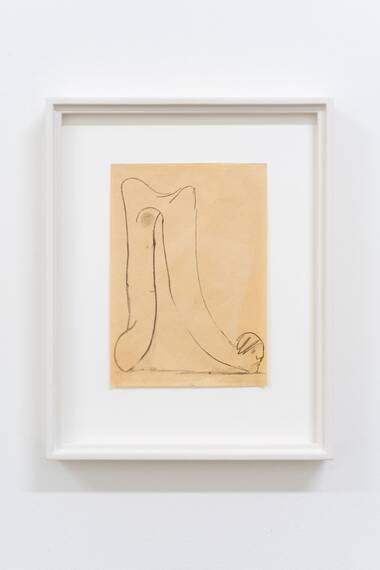

Mark Barker’s work speaks of bodies, how things move in and out of them. Characterised by considered material investigations, his multi-faceted practice spans sculpture, drawing, painting, photography, and video. Increasingly, Mark employs widely accessible and mundane materials, such as bread, oil, and other domestic substances. These material choices, coupled with his diverse conceptual approaches, articulate the concreteness of bodily experiences – digestion, desire, anxiety, shame – while probing the mechanics and limits of living alone in a body.

His subjects are in a persisting confrontation of form and collapse. Through brokenness and decay of the animate and inanimate – by way of leaks, cracks, waste, and fluids – Mark proposes and embraces the body as porous and messy, potentially limitless, and in need of support.

Mark’s drawings and sculptures are developed through imagination, observation, and careful research, with sources ranging from sanitary design to human and animal anatomy. In his works on paper, the bodies are often leaking, disfigured, and somewhat exposed, broken to the point between slippage and containment. His sculpture often reimagines the figure as a body of parts, strangely reduced and exaggerated simultaneously. There’s an inherent element of care in these, inscribed through the process of making.

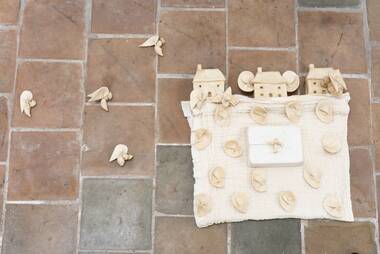

In Are you more (2024), Mark presents a taxonomic display of objects, crafted in bread, more or less. These include wasps, human ears, buttons, cottages, and flowers, and are arranged by type on the floor of the gallery, which was once the site of a bakery. Through this work Mark attempts to articulate how we organise and classify the world around us, drawing attention to the ritualistic, and at times obsessive, acts that shape our domestic and cultural practices.

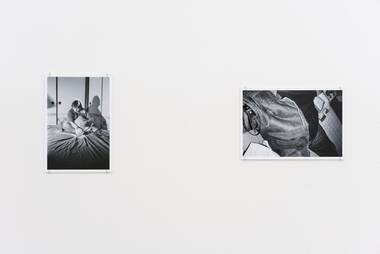

The photographs by Libuše Jarcovjáková selected for the exhibition represent just a small part of her systematic record of herself. Libuše began to photograph herself at the age of 16; at present, her photographs stretch across 56 years of her life. With a need to not disrupt the succession of her own images, she places herself in the centre of her attention. She often records herself repeatedly and opts for volume of images rather than reduction.

It is as though the photographs were not created primarily with the awareness that they would be shared with an audience. They are created with a certain detachment from the self. She tries to manipulate her appearance and expression as little as possible, minimising the aspect of self-judgement and self-evaluation and documenting herself without regard to the changes her body has undergone over time. For the artist, the act of photography represents a link to the present, and the act of looking at the photographs after the fact serves as evidence of her existence in a given place and time. They are means of both introspection and grounding in reality. They are methods of coping and establishing a relationship with oneself, of feeling the closeness and distance of one’s own body.

Also on display are portraits of Libuše taken spontaneously by some of her close friends with her camera. Without calling their authorship into doubt, Libuše places these among her own records. Self-portraits created with a tripod, which she rarely uses in her work, can be seen as a special event in which the artist has tried to express her emotional and physical state or capture herself in a crucial life situation. Instead, Libuše’s work consists predominantly of self-portraits taken by hand with a camera aimed directly at herself or at her reflection in a mirror. For the artist, these represent a record of herself without any additional layer of meaning.

One of Zuzana Šrámková’s first photographs, from 2010, depicts two young girls bearing a marked resemblance to one another seated in identical armchairs posing in reaction to the fact that they are being photographed by someone close to them. One girl has a turned head on a contorted body, while the other balances the feral composition with a gesture of silence. It’s a funny and also harsh physical scene implying close contact with the person behind the camera, who is having a good time in conspiracy with them. This photograph is a foreshadowing of sorts for all that came after.

The interest in physicality in Zuzana’s photographs is more of a natural component of their environment than a plan. Life in an open community of young people in the subculture of Ostrava has enabled openness, affinity, and closeness through shared experiences, views, self-destructive tendencies, exposure and physical contact, hanging out outside, parties, playfulness, fun, music, tobacco, alcohol, and other substances. Zuzana’s photographs show the vulnerability and, at the same, resilience of bodies. These bodies are formed by togetherness, a demanding social life, and the environment in which they live. Some of her photographs are almost sculptural in nature, evoking nude bodies and objects referring to volumes, movements, and the energy within them.

Zuzana is a part of the group of people she photographs, standing too close, intentionally not trying to step to the side, focusing more on the experience itself and her participation in it. To her, objectivising documentarian approaches are an obstacle for capturing something that only exists within a shared experience. Unlike Libuše, Zuzana is not in the centre, but stands with evident understanding at the edge of what’s inside. She works with a range of image quality and in high quantity, which strengthens the intensity of her individual photographs. The technical and pictorial perfection of her work is not intentional, but rather a consequence of impulsiveness and lightness – leaving things and events as they are.

Zuzana Blochová

---

the things that are left

(For Mark II)

I was living alone when I wrote about Mark’s work three and a half years ago, seeing a man whose politics and routines I hated and not getting off enough for it to be worth it. It was, as I had speculated in the text, a reaction against a year of aloneness, a revision of a solitary life. You could call it infatuation, which can so quickly turn into revulsion at oneself. We fell out eventually, over Israel’s occupation of Palestine, but we are still strange friends, I think.

I don’t live alone anymore but I haven’t moved. It’s been a year and a half with my girlfriend living here too. Her rhythms and routines have brought stability and joy. But I push against them by staying up too late and drinking alone since the death of my dog. I have romanticised the sense of freedom I had when I first moved here, into my stepmum’s empty house, just me and her (the dog), the rooms almost empty of things, no real weekends or weekdays, a bended kind of time. I didn’t even have my books when I first arrived – they were all still in the flat I once co-owned and had to leave. The slow accumulation of dried plants and objects – along with all the books that arrived in boxes from the flat, but not all the furniture that I want back – now accumulates dust and spider webs. (The new dog has chewed through all the pinecones and teasel stems, creating a layer of indoor mulch.) It was here that, for the first time in many years, I drew and painted. I pressed plants and read about their medicinal properties and cultural histories, and then learned to dye fabric with them. I made a garden. I sewed panels of dyed fabric into curtains. I made quilt tops. I embroidered. I thought I was remaking myself, learning to take up space. Four years on, I feel unmade, unravelled, failing at doing my work, feeling more isolated in this world that has reconnected without me, or not – I wouldn’t know.

I want the lessons I have learned about taking up living-cum-studio space to inhabit me forever, I wrote in that text. Mark had been making sculptures in his Berlin apartment, living with them like flatmates. For the first time in a long time, I feel like I have a whole body, not a body of parts splitting open or tearing themselves away from each other. I don’t know how I feel now – maybe like the parts are fusing together, bonded to something like a family, but queered. This is something I want, but I still feel the need to tear away from. (Re)productive time, family time, is also something I want to destroy.

Mark still lives alone. Unlike me, he has maintained his self-sufficiency, in homemaking at least, self-sufficiency being a concept that masks the reality of interdependency, having a committed partner and friends, people to care for you, and who you care for, within the realities of a culture of extraction, of so much labour for such little reward. Mark’s drawings describe the feeling of being one of many, part of a social body, and how cut off or separate you can still feel despite this. He uses the metaphor of a body-in-parts, a body struggling to hold itself up. Heads are too heavy; they need support, and sometimes their weight is held by other body parts, an act that seems impossible to maintain. In Under the weather, a (2021), a person has become the components we all know are underneath our skin: sacks of organs, abstract forms that weigh down on the head, shit coming out of the mouth. In as yet untitled (headache) (2020), a singular body has grown its own support to rest its head on; the rest of the body has been sacrificed. This fragmentation or extension describes the effects of being alone, or solitary, on the body, how we feel the labour of just existing as a strain.

I feel like a different person depending on who I’m spending time with, whether I am alone or in company, and Mark’s drawings also remind me of this feeling, that we’re holding so many versions of ourselves in our bodies, and some of them weigh heavier than others. Some of them are absolute nightmares. London bend (2016) is a decapitated head and neck being held up by arms, on its knees. 2016 – is that when we lived together? I can’t really remember. I moved there when I had to leave the first time. We were different versions then.

Living alone costs more than living with a partner, literally. Single people are less financially resilient, even if they are more emotionally self-sufficient. When I lived alone, and I was single, I felt released from the rules of gender and sexuality, the tyranny of the couple, of heterosexuality and womanhood, but that doesn’t mean I was free in the eyes of others. Nothing had actually changed, I was just avoiding plain sight. As José Esteban Muñoz writes, “To be lost is not to hide in a closet or to perform a simple (ontological) disappearing act; it is to veer away from heterosexuality’s path.… Being lost, in this particular queer sense, is to relinquish one’s role (and subsequent privilege) in the heteronormative order.” We need to be lost to the logics of reproductive futurism in order to imagine a future of queer kinship. Coupling is like making a new version of yourself, but all the other ones are haunting you.

Sometimes you have to get away. It’s like Libuše says in the feature documentary about her work:

I feel like I could achieve a lot in my life but I fear I might screw it up.

“Now it’s not the right time for art,” my mom says…

Why can’t I just live my life the way I want?

Libuše has recorded her life in diaries and photographs since she was a teenager, producing the kind of evidence of queer lives that is so often unavailable to us in the present. In the early years of the AIDS epidemic, 1983–85, Libuše photographed the clientele of T-Club, where gay men and women gathered in Prague. Libuše’s subjects were her friends, recorded as an insider, taken over many months. The photographs are full of joy, drinking, coupling and freedom.

Diaries and photographs are the kind of evidence that can be used against you. Muñoz again: “Historically, evidence of queerness has been used to penalise and discipline queer desires, connections, and acts.” Photographs can quickly turn into physical evidence of transgression: Libuše was once asked by the police to show them a roll of film had taken the night the person was murdered, a reason why she stopped taking photographs at T-Club. In light of this, Muñoz argues for suturing queerness to the concept of ephemera, the trace, the remains, “the things that are left, hanging in the air like a rumour.” This is the real subject of Libuše’s photographs – queer knowing, moving and feeling that happens in the club, or in a couple’s bedroom, even on your own in the bath, away from the “harsh lights of mainstream visibility and the potential tyranny of the fact.” In an interview about the documentary, I'm Not Everything I Want to Be (2024), she recites a Czech saying: “It’s always darkest under the light.” It’s hard to see what is closest to us, even if it is visible to others. What is most hopeful – a queer future, say – has its hidden or negative aspects. In order to live on her own terms, Libuše had to leave Prague, and go to West Berlin, formally in West Germany, in 1985. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, she returned to Prague, where she still lives with her wife.

Libuše’s photographs from the T-Club are imbued with wilful collaboration, made with her friends and lovers in the moment. They are ephemeral moments that the camera, when in the hands of an insider, a lover, can enable and transform. We see the remains of queer acts that can happen inside, beyond “the cool look of a street cruise, a lingering hand-shake between recent acquaintances, or the mannish strut of a particularly confident woman.” Libuše’s camera captures ephemeral performances of queer freedom under a totalitarian regime. The photographs are evidence of queer lives under siege, which must usually keep hidden from the camera’s flash to avoid exposure. Libuše turns the camera, a tool of surveillance, into one of resistance and legacy construction, capturing the pleasure and freedom that can be sought out in the underground.

Zuzana’s photographs document a social scene under threat from the mainstream, the punk music scene that formed in Ostrava, in the north-east of the Czech Republic, around a street called Spodní – “the bottom”. As a community, they lived in buildings in that socially excluded area in return for repairing their apartments. Like Libuše, Zuzana photographed this scene from the inside. Zuzana’s photographs are a call to imagination, providing tiny glimpses – a relationship dynamic, a room, a night, an act – of the individual life experiences that brought these subjects together. She produced texts for her bachelor thesis, a 2015 photographic book, which articulate the project as a kind of challenge to the viewer, but also to the kinds of documentary practices that photograph excluded communities, such as Roma people who lived in the area, as other to themselves. “Let’s work with them, live alongside them. Let’s imagine where they come from, how they are treated, what they pass on in their families, what kind of attention they get from their parents, how they can’t get rid of stigmas.” Zuzana documented her own community, turning the camera inside rather than using it as a weapon to exclude and objectify.

The photographs Zuzana produced function through accumulation, a mass of alcohol-infused moments of collectivity and kindness as an act of survival. The lives of Zuzana’s friends and acquaintances are documented en masse, hanging out, holding their cats, eating, drinking and smoking – sometimes all at the same time – and resting, asleep or passed out. The characteristic blur of the snapshot enhances the spirit of her subjects, who are unserious, anarchic and young. Captured by Zuzana’s analogue camera, her subjects live out their everyday lives, holding each other up, sometimes literally. They roll around and hug, relax and laugh, partying in dive bars or the squat buildings, naked with dirty feet and laptops. Sometimes they pose in relaxed groups. Bodies contort and slump. There are so many of them. Each image, like each person, contributes to the whole, like a collective, a social body in flux.

Mark’s live-out partner takes him on walks every Sunday afternoon, a beautiful act of care. L and I circle through less than a handful of places to walk at the weekend. The house is near enough to heath, woods and cemeteries on the edge of the city. These were places I walked with the old dog – the dog who died but who wasn’t old. On these walks, I looked up plants and trees I didn’t know the names of, and I still do this. Some I gathered and pressed or made dyes with. Some of these places are where I walked with my friend, part of a couple who “bubbled” with me. He would drive all the way from South London and we would get drunk and watch horror movies and then walk the dogs in the woods the next day, the pair of them screaming around after the squirrels, my one often refusing to come back. We worked out how to catch her by standing apart and kind of herding her somewhere enclosed. Eventually, she would run from one of us into the other. The new dog is shy, far more cautious. She runs fast but stays close. The old dog who wasn’t old when she died was a symbol of my self-sufficiency and unattachment. She was my dog, but she was also not separate from me, more like an extension. The new dog is our dog, together. What would she be doing if she hadn’t met me? Maybe she would have found a better way to spend a Sunday afternoon.

In between working on other pieces, Mark has made small sculptures out of white bread in the studio. White bread is trash food – not nutritionally beneficial, all the fibre removed. Here it is a kind of studio detritus, a miniature architecture made out of a mixture of the materials he uses for sculptures and drawings: adhesive, plastic, beeswax, plaster, graphite and food colouring. (Scientists have been trying to work out how to make a healthier version that still tastes like white bread by adding peas and beans.) The forms are small: pellets rolled up in the fingers, cut-out houses as a child would draw – one with a head or a flower, one with ears – and some more abstract shelters. They somehow represent all the time that is spent producing work, all the breaks when your thoughts are elsewhere. This is studio time, unproductive time, queer time.

The house we live in is full of our things and our pets but it’s still just a container – not mine or ours, not permanent. At times it feels like a trap – and the only way to stay in this city, which is not Prague or Berlin or Ostrava, but London. It feels as if, at any moment, we will have to pack it all down and leave. So many of us have already left. Where will we go? Possibilities arise in our minds – another city that is cheaper, maybe nearer my mother, or a different edge of this one? – but these too are transitory, lapsing. Home is just an idea, a cut--out. It can be rolled up in the fingers like any other thought.

Alice Hattrick

London, December 2024

Translations and language editing: Václav Mlčoch,

Guy Tabachnick

Thanks: The Emblem Prague Hotel, Edith Jeřábková, Daavid Mörtl, Lenka Vítková, Shahin Zarinbal

The program of the Cursor Gallery is possible through kind support of Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic, Prague City Council, State Fund of Culture of the Czech Republic, City District Prague 7,

GESTOR – The Union for the Protection of Authorship

Media partners: ArtMap, jlbjlt.net, artalk.cz and ArtRevue