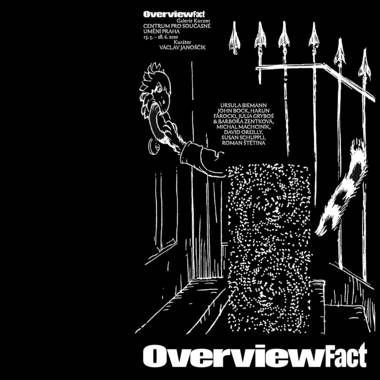

Overview Fact

13. 5. – 28. 6. 2020

Ursula Biemann, John Bock, Harun Farocki, Julia Gryboś a Barbora Zentková, Michal Machciník, Susan Schuppli, Roman Štětina

installation in the courtyard area: Michal Č. Šembera

curator: Václav Janoščík

Download the exhibition brochure here

Chapter one

What if we are living in a detective story?

It seems that problems pile up, multiply and threaten constantly; increasing complexity allied with growing uncertainty, the accelerating incursion of technology and the never-ending mediatisation of reality, marked with the lack of our ability to keep up, orientate and navigate. As if the very idea of contemporaneity, our world or the current condition seems to be at odds, obscured, veiled, and even ominous. As if the contemporary is determined not by ideas and values, but by those very problems, disorientation and the lack of consensus or common ground.

If I were to put all of these issues into a detective story, it would not be a traditional quest to solve the problem, to discover and detain the criminal. Because in many cases we KNOW what is wrong (with climate change, the resurgence of xenophobia, populism, the undermining of the role of knowledge or even truth). What we lack is structure and agency – be it the figure of the detective, the ability to deal with the problems and to do something, or even the very story-like form that could be widely shared.

I cannot but think of Christopher Nolan’s movie Memento (2000), where the viewer struggles along with the main character to grasp even the most basic structure. Not only the movie unfolds in reverse, but his lack of memory drops him into never-ending uncertainty. Also the denial, delusions and disorientation are in the end self-imposed, as are most of our ecological and social problems.

Detective fiction usually involves a dialectic of unknowing and knowing, as much as a dialectic of crime and justice. What we know is haunted and propelled by what we do not know, usually in order to discover the enigma of crime in the end. In Memento, Nolan accelerates this detective engine. The unknowing spreads rather than the other way around. And in the end, even though there is a cataclysm, it is the beginning, the cause – not any solution or reconciliation – that we get.

Maybe our current time is marked by similar “acceleration” or hauntology. Instead of moving forward we are stuck in the past. Instead of generating more understanding our current information ecologies are driving us apart. This is what motivates anything I do. How to readjust, use and fight the current economies of knowledge? How to revive some substantial sense of contemporaneity? One presumption I work with is that we need to save and work with pop culture, as that is what generates traction and common interest.

And detective fiction may provide topical knowledge, since it is not only one of the most popular current genres, but also involves narratives of justice, commonality, restoration and agency. Conversely, in contemporary art we often talk about the forensic turn, the new challenges of documentary approaches, the relevance of facts; and of course their intersection with fiction.

Work of Roman Štětina, Ztracený případ (Lost Case, 2014), is resplendent with these references. He follows detective Columbo as he goes from one place to another, comes in and out without solving anything. His movement and the sequence of solved cases seems seamless and swift. Yet the inability to talk, to act unsettles and disquiets me a lot.

While his career from 1968 to 2003 evolves, we are confronted with movement, steps, arrivals, shifts, props and duration. Tension and suspense keep piling up without release. An overview without the fact or reference.

Chapter two

How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Overview!

I dream of a general, holistic or even wholesome perspective. If only we could be someone else, or anyone at all. Isn’t that the crucial paradox of any democratic polity. We want to be impartial, to speak from a universal place, yet we are deeply biased, always already at some specific spot within the social architecture.

Yet we have a name for this human heresy, the ultimate lookout. It is the overview effect, described by many astronauts looking at Earth from outer space. Getting literally the whole picture, a complete distance producing intercommunity.

Unfortunately most of us don’t get to spend time on a space station. We must remain here, stuck with all our issues. An orbital perspective remains an effect for us. But we have means of transforming it into an overview fact. We can make the effort to do the detective work, to orientate, investigate, trace and track our surroundings.

From among the spectrum of investigative methods Susan Schuppli chose trace evidence. This refers to the transfer of particles, provided through contact, friction or co-presence. In the video of the same name from the year 2016 she follows radiation across the Pacific Ocean from Fukushima to Vancouver.

Along the path of the Caesium-137 particle we have time to ponder the importance of material circulation and complex interconnection, as even we are just particles of planetary-scale systems. Ursula Biemann submerges us in the ocean in her video Subatlantic (2015). This presents not only a huge ecosystem, but a living body, flows of matter and energy, the subliminal level of our ecological problems and hopes.

Going onto orbit mirrors being submerged in the ocean. While the horizontal axis follows geopolitical boundaries and populated areas, the vertical movement grants us access to different levels and strata (Deleuze, Guattari). The vertiginous and exorbitant feeling from these depths and heights can be scary and still carry a hope. Even climate change can be the universal cause that can set our common ground.

Vertical jumps and horizontal affiliations – this is precisely how you can move between layers of being in the remarkable game Everything (2017) by David OReilly. Here you can be a sheep, flower, rock, atom, or an entire galaxy. You can simply move, meet other entities or “sing” and “bond”. It feeds you with both a potent and productively naïve vision, often articulated by Alan Watts.

As such the game gives you an overview on so many levels. It presents a processual ontology, where the agent is always in relation to an environment, its inhabitants, irrespective of their scale, origin or character. Exhibited along with more traditional “works of art” it offers an opportunity to re-evaluate our expectations from art spaces and the engagement they provide, as well as the very status of gaming.

Similarly, the current coronavirus epidemic, besides its dreadful consequences, may force us to think about a different world, in which GDP, endless progress, consumerism, cheap flights or constant acceleration can recede in favour of different values.

Chapter three

What the woodpecker left behind the paraván?

Screen and woodpeckers are peculiar beings. They both make a division between inside and outside, between what is visible and invisible. In the case of a screen it is the private taking refuge behind, while woodpeckers pull the inside, the bugs and pieces of wood, out.

We see that quite instructively in Michal Machciník’s straightforwardly titled Pocta Ďatlovi (Tribute to the Woodpecker, 2020). Assemblages of wood, polyurethane foam and epoxy resin present the inside, yet they are visible. As evidence of intrusion, rupture, a hollow or even a nest.

Both these processual objects and the thresholds they present are so frail. They make me think about our interference with nature, about the chains of changes in the dynamic equilibrium of each ecosystem. As if these assemblages bear witness to us, tireless woodpeckers pecking the world out of its place.

Julia Gryboś and Barbora Zentková work with fabric, volume and abstraction along the lines of similar logic. Diagnosis of the Curved Spine (2019) takes the form of a screen, or so called paraván, usually used in an urban dwelling to create a safe zone, to hide the intimate, dressing/undressing perhaps. As such they immediately point beyond themselves to the space and its status.

What is it that should happen behind? What is it that hides and eludes? Maybe it is the lost spirit of the bourgeoisie, for which screens were intended, as well as the purchase of fabric for custom clothing or interior design. Perhaps it is the circulation of materials that marks our age of the Anthropocene, where the industry of fast fashion is both deeply disruptive and thoroughly seductive.

But maybe it is still the woodpecker, the detective in play.

Both installations work with distance. Not only do they force us to navigate, to attain an overview that transcends the usual gallery setting, but they also involve a dynamic way of looking at them. The interplay between detail and the whole draws me in and out. Like a detective getting from the case itself and overall motive to the trace, a small lead and back to the identification of the criminal.

Machciník works with natural processes of growth, intrusion and intervention. Gryboś and Zentková on the other hand use highly cultured dynamisms of hiding, showing and dividing. But both allude to different usage of materiality and art. Objects generate traction, they are not just sculptures to be seen, they present evidences to be traced and constantly pushed further.

Final chapter four

If YOU were detective and not the victim …

There is a word in the global art world that has perhaps received more attention than any other in recent years. It is forensics, with its emphasis on documentary practices, archive, contested areas, unrepresented problems or critical engagement. Here we trace a slightly different forensic trajectory that may well be presented by the last two artists, HarunFarocki and John Bock.

The first maybe seen as the inventor of a forensic art practice, analysing the way in which modes of representations influence and form our conception of the world or our identity (from television to military 3D simulations, from football to a necropolitical vision of war drones). John Bock on the other hand takes forensic scope into the context of objects, materials, rituals, storytelling or intimacy.

This is the spectrum running from Farocki’s well known and utterly serious video Nicht löschbares Feuer (Inextinguishable Fire, 1969) to Bock’s playful Skipholt (2003), which maps his visit to Iceland. Farocki is concerned with the Vietnam War, suffering, and the limits of its representation. Bock wants to engage with the deeply personal and imaginative role of video and story-making.

Nonetheless both authors work with the explicitly singular experience, its excess, and its power to affect and to be shared. They remind us how our reality is based around our desires, how the documentary immediately invades the imaginative, how truth can be fought and constructed through fiction, and how important it is to get involved with the productive process, be it the manufacture of napalm used in Vietnam, or the creation of navigable spaces and landscape.

One way to frame forensic focus in art is to elucidate its will to transform and deepen our engagement with the real (as opposed to the construction of fantasies). But we must be ever more specific in this respect. The forensic gaze turns to affects, materials and nonhuman entities besides stories, people, wars and conflicts.

As if we are all just living bodies linked to machineries of the visible. In Farocki’s view this is a political urge– how to present the horrors of war, or the under- or mis- -represented agents of our world. Bock again tries to work directly with this affect-making machine that we usually define as story.

Narration, mediation, collective affection – these are the challenges of our world in the 21st century, resplendent with complexity, problems and crises, but also traces, connections and meanings that are worth our detective scope. Let us accept the challenge and create and share something we carelessly call the world or contemporaneity. Let’s generate overview for fact.

“You want people to have that shift in perspective, to think planetary. You want them to come out and solve problems in context of the real world in its entirety, to solve multi-generational problems, not slap band aids on things.”

Ron Garan, The Orbital Perspective

“A book of philosophy should be in part a very particular species of detective novel, in part a kind of science fiction. By detective novel we mean that concepts, with their zones of presence, should intervene to resolve local situations.”

Gilles Deleuze, Difference and Repetition

“Our insistence on forensis rather than forensics is meant to engage with the present, with current political processes – not with a dead body under the microscope but rather a living one twisting under pain – this requires political understanding and political intervention.”

Eyal Weizman, Forensis is Forensics, where there is no Law

“When napalm is burning, it is too late to extinguish it. You have to fight napalm where it is produced: in the factories.”

Harun Farocki, Inextinguishible Fire

“See, now there you go. You're looking at your watch again.”

Columbo, Short Fuse

“In everything that can be called art there is a quality of redemption.”

Raymond Chandler, The Simple Art of Murder

“I was as hollow and empty as the spaces between stars.”

Raymond Chandler, The Long Goodbye

The programme of the Center for Contemporary Arts Prague receives support from the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic, Prague City Council, State Fund of Culture of the Czech Republic, City District Prague 7

partners: Kostka stav

media support: ArtMap, jlbjlt.net and UMA: You Make Art