Dystopian Realism

15. 7. 2020 – 6. 9. 2020

opening: 14. 7. 2020 from 6PM

artists: DIS, Max Göran, Jakub Choma, Sarah Lüttchen, Agnieszka Polska, Jonáš Strouhal, Dušan Zahoranský

installation in the courtyard area: Michal Čeloud Šembera

curator: Václav Janoščík

Download the exhibition brochure here

Chapter One

The End of the Future

Growing up in a small, post-industrial border town I well remember running home in order to catch the latest episode of Star Trek. At that time Czech Television was running the second series, New Generation (1987–94), in which the crew of the Starship Enterprise was led by Captain Jean-Luc Picard. The universe in which the series was set combined the ideal of an enlightened civilisation without conflict, the cosmos as an infinite space for exploring and understanding the unknown, and a society without money in which resources were available to everyone. It was in some respects a kind of communist utopia that, paradoxically, meshed perfectly not with only my childhood but the capitalist transformation of the Czech Republic during the 1990s. After the pop culture of socialist Czechoslovakia, with its heroes, aesthetic and values, had been discredited, a vacuum appeared that had to be filled with new stories and mythologies. The story of unproblematic multicultural coexistence, a warp-leap into an idealised future full of opportunities, drew on this potential.

But the seemingly stable world of Star Trek has changed dramatically in recent series. This year’s Star Trek: Picard (2020) returns to the character of its eponymous hero. In the opening scene we see him playing poker with Lieutenant Data in the command centre of the Enterprise. He hesitates before making a play, and when Data asks him why, he says he doesn’t want the game to end. A moment later the entire cabin is swept away by an explosion. The former captain awakens from a dream in his vineyard, without starship or crew, no longer boldly going where no man has gone before, bereft of his trademark self-confidence and ability to act or give orders. It seems that the game that ends in his dream is not a round of poker, nor perhaps is it a recollection of his now deceased friend Data. Perhaps it is a game of utopia, which, like poker, depends on the ability to bluff, to convince someone of the reality of cards and ideals that you by no means have to have in your hand.

Though the new series retains many of the ingredients of the original Star Trek world, it is no longer driven by the grandiose project of space exploration. Nor is human society any longer as confident in its mission, unanimity and peaceable intent. On the contrary, it is marked by conspiracies, conflicts and a traumatic past. It is as though the original utopian structure had been ground down into fragments of dystopia. As if the future were inhabited by problems and fears rather than plans or visions.

Chapter Two

To Speak of Capitalism

One of the most frequently repeated claims of contemporary philosophy is that “it is easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism”. Whatever our political convictions, this statement says something fundamental about our political imagination and about the future and our ability to share it. We lack alternatives and visions, as if we really were at the end of history as described by Fukuyama, and were forced to repeat or prolong our present. However, the word “imagine” in the statement above refers not only to the future, but also to the imagination, narrative and fiction. It is stories and art in general that should forever be pushing at the limits of our imagination, expanding the possibilities we reflect upon and long for or fear.

At present there is a battle being waged for our future. Conservatives, populists and right-wingers – even the most extreme and reactionary – are reconciled to the end of the future. They live in a world whose clear outlines (state and cultural borders) and above all identities (national, familial, religious, but also gender) are being atomised and lost. Perhaps their most common reaction is to turn to a more or less idealised past, in which “everything had its place” and there was no doubt about who was Us and who was Them.

In contrast, the second camp, usually associated with the liberal left, still wishes to continue various emancipation processes and therefore unavoidably sees the future as open to other possibilities. Our social time is being torn to pieces in this struggle, in which some want to move forwards and others backwards. I find myself wondering how to speak of capitalism in such a situation (so as to avoid simply lapsing into leftwing criticism and rightwing silence). And what role should art play in this talk of capitalism?

Chapter Three

Close Dystopias

Mark Fisher, who popularised the statement above, associates it with what he calls capitalist realism, which he defines as “the widespread sense that not only is capitalism the only viable political and economic system, but also that it is now impossible even to imagine a coherent alternative to it.” But today, more than a decade on from the publication of Fisher’s Capitalist Realism, the situation is somewhat different. An increasingly large spectrum of people are willing to think critically about capitalism. Problems are not only multiplying, but are being placed in context. It no longer suffices simply to point to the limits of this social imagination (Jameson, Žižek, Fisher, Berardi, as well as the art of Claire Fontaine and Bernadette Corporation): increasingly thought is being given to the world after capitalism (McKenzie Wark, Paul Mason, Metahaven, Postcommodity, FutureFarmers).

In 2009, when Fisher published his book, capitalist realism could be perceived as a consensual, society-wide structure. These days cracks are appearing in this global structure. There are growing tensions, especially between those who continue to climb the career, financial, affective and aesthetic ladder, and those who are reacting to the structural problems of the entire building, from ecological crises, via neo-colonialism, to the toxic effects of consumption on our identities and ability to share.

Our coexistence with capitalism has increasingly darker outlines, from the ubiquitous signs of global climate change, via the increased incidence of mental disorders, to exhaustion and anxiety, which reach the very top rungs of pop culture (from the Xanax rap of Lil Peep and Yung Lean to the nostalgic pop of Lana Del Rey and Adele). I believe we are fully justified in speaking of a kind of general dystopian realism. After all, dystopian stories, films and serials themselves do not appear to inhabit some distant future, but the here and now.

Perhaps the most striking example of this trend is the series Years and Years (2019), a British blend of family relationship sitcom and a dark vision of the near future. The Lyons clan from Manchester experiences personal, career and psychological drama framed by the melting of the last iceberg in Greenland, the use of deepfake manipulation, the spread of xenophobia, and the return of disciplinarian and totalitarian techniques of power throughout Europe. What is shocking is not the speculation regarding politics, but the realism being stretched between the fictional world of the serial and our current reality.

Chapter Four

Distant Reality

It is the concept of realism that is crucial in this collocation. The word usually refers to the endeavour to “represent reality faithfully”. But after two centuries of critical philosophy (from Kant via Benjamin to Barthes and Flusser) we know that the world of representations, our culture, is in many respects creating its own reality rather than faithfully corresponding to some objective physical reality. Realism relates not only to the world as it is or was, but to the future; it is not simply a description, but also a desire and an expectation. Every culture creates its own realisms, i.e. great endeavours to describe and decode, as well as to influence and create a shared reality.

Jacques Lacan claims that reality also obscures the Real. Reality is a filter, a symbolic order that orients us, names things and relationships around us, and embeds us in the world. In contrast, the Real lurks in those corners where reality, description or explanation fails. It is that which we are scared of in a horror story before we even know what it is that is scary. It is the fear of something beyond our ability to recognise, orient ourselves around, or understand.

If capitalist realism means (pop)-cultural attempts to hide problems beneath a sweet, glittering surface, then dystopian realism deals precisely with those fractures, fissures and rifts, the places where the surface suggests tension, anxiety, or conflict. It does not have to be “dystopian”, or even dark or future-oriented, nor does it have even to be critical, activist or sad. On the contrary, it can often seize the opportunity to articulate affective, strong and positive language. It is an effort to create and live with the problems of our world.

Chapter Five

The Desert and Dying Cars

Bikers riding through the American desert, mangy animals, the geographical and social outskirts of Los Angeles, monster truck races... all this and more is to be seen in the video installation by Max Göran Assholes Live Forever (2019). The title itself combines disillusionment and hope, self-doubt and arrogance, outsidership and salvation. Images that I seem to recall from Mad Max or some other dystopian world are vividly connected with our own present. They are not a dark vision of the future, but a flash of freedom and escape, a strange and paradoxical moment of happiness frozen out of the mainstream hit parade of consumer values.

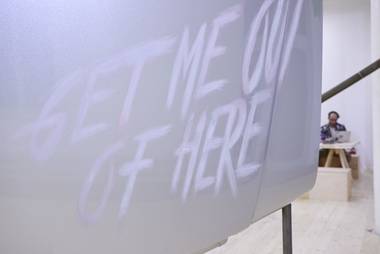

In a similar fashion Sarah Lüttchen uses car bonnets (hoods) found in junkyards. This is not just about slogans and pop aesthetics, but also about the real stories concealed beneath each bonnet. Cars were present at the birth of our fixation on the future. In 1908 the Ford Model T, the first mass-produced automobile, took to the muddy roads of America, and in the same year Filippo Tommaso Marinetti wrote The Futurist Manifesto. Civilisation rushed into the short 20th century, framed not only by the First World War and the end of the Cold War, but also by the belief in the future and utopia.

These days we regard utopian stories and programmes as naive, or even completely discredited by the collapse of real socialism, which people mistakenly associate with the utopia of communism. And so Sarah Lüttchen’s car bonnets feel like a kind of farewell to the era of oil and the future. Cars and motorbikes will no longer propel us into a better tomorrow, but perhaps only to an abandoned junkyard or the deserts on the outskirts of Los Angeles. We may one day think of the current situation as a period of escape and dystopia in which entire ecosystems perish, while motorbikes, cars, outsiders and assholes dream of eternal life.

Chapter Six

The Worst Joke in the Universe

It would seem that dystopian realism supports a certain heroism. Or perhaps more the heroism of escape. There is enthusiasm and energy, but it is not used, it crackles as in a turbo-diesel engine, it is full of a beauty that has no purpose or programme. All that remains is to watch. It is the role of viewing and the inability to act (from global climate issues to internally divided societies) that is the key to the present and is the theme of Agnieszka Polska’s video The New Sun (2017).

Observing from afar offers us a certain comfort and distance, but can also be dangerous. It forces a perspective on us, along with everything that comes with it, our opinions, our entire world. When we look around, it can easily seem that everything is hunky-dory. People search out shade, converse with one another, cars and trams continue to run along the same routes. But the sun, to pick an example, is looking at the disintegration of our system, the environmental, perhaps even the political. It sees my fingers, dogs on the street, your surprised expression. And if the sun could speak it would say: “Everything is gonna be fine.” Even though it knows that’s not the case.

Empathy, which used to represent an emotional and psychological relationship, is fast becoming entangled in politics, in our ontology. Am I able to empathise with the sun, with ecosystems? With people with whom I disagree? In 2018 Jonáš Strouhal travelled to the centre of Prague dressed as a “sad Alza alien”. Wearing the costume of the largest Czech electronics retailer, he wandered up and down, sat by the National Theatre, and observed his surroundings helplessly. In response he received uncomprehending looks, anger, threats, fists... as well as solidarity and the offer of food, and even a message from the marketing department of the company whose mascot he was wearing, Alza.

It is as though we had become unwelcome participants in our own stand-up comedy. The public space, the relationship with the environment and the consumer culture are becoming a long and tedious joke. We can heckle all we want, but it is we who are standing on the podium.

Chapter Seven

I know I’m Speaking in the Abstract

One of the biggest paradoxes today is the tension between an ever flattening, simplifying language (under the pressure of intelligibility, efficiency, managerialism, and global consumption) and a complex, fragmentary communication system or network (from contradictions and media bubbles, to conspiracy theories, hoaxes, post-truth and information wars). It turns out that abstraction and collage are not simply traditional artistic strategies, but that more and more we have to use them in everyday life and communication. We adapt to the overwhelming pressure of our “attention economy”, we abstract and simplify, thoughts and feelings give rise to phrases or slogans, philosophy and art to marketing. On the other hand, there is an ironic game being played of reference and multiplication, desire, appropriation and simulacrum.

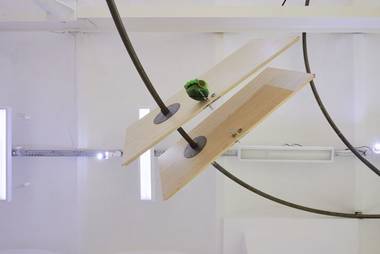

The first direction is illustrated in the installation by Dušan Záhoranský Libor, Věž Sémiokapitalismu (Libor, A Tower of Semiocapitalism) (2019). The circle forces me to look around, to stop and connect things. Metaphors of circulation, cyclicality and the circle that we associate with capitalism, the alternation of labour and consumption, the free movement of goods, capital and people, absolute deterritorialisation, complex interconnectedness and the simplicity of the circular shape.

In contrast, Jakub Choma uses his own tableau from the series Living the Gimmick (2018) to combine many different elements, ranging from materials, via symbols, to short mantras that can be linked just as easily with capitalism as with its radical critique. The surface of the image flexes its edge and even stretches out its hand. It gestures towards another serial, a political movement of hidden desire, to the recycling of materials and ideas, from the world of painting and imagination to our repetitive and spectatorial reality.

Chapter Eight

The Emancipation of Dystopia

The DIS collective works in a very similar way. The videos on their portal dis.art avail themselves of the space of contemporary art, 3D visuals, commercial aesthetics and the critical capital of contemporary thinking in order to attack the many fronts of the current struggle with capitalism. This can mean ecology, the precariat, the anaesthetics of consumerism or identity politics. dis.art mobilises criticism of the present and furnishes our knowledge with the weapons of art and marketing.

Criticism side by side with crisis, art hand in hand with politics, the gaze alongside the inability to act, your ego in concert with identity politics... these now make up the ambivalent and beguiling wallpaper of the living room we call the 21st century. We need to be careful about whom we invite home. They might destroy our planets or change our life. They may be more critical (of capitalism, of us) than is appropriate. Dystopias represent such an unwelcome and disruptive, yet entertaining and these days familiar, guest.

Inasmuch as rightwing politics and mainstream and consumer culture have discredited utopias, it is time to return to dystopias. But not with fear or caution. On the contrary, we must seek a friendly, intimate relationship with them. If, until recently, one could say that we live in “the best of all possible worlds”, we are now in a position to face up to the profound problematicity and coarseness of the contemporary, and view it as a challenge to continue the struggle.

Václav Janoščík

(transl. Phil Jones)

The programme of the Center for Contemporary Arts Prague receives support from the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic, Prague City Council, State Fund of Culture of the Czech Republic, City District

Prague 7

partners: Kostka stav

media support: ArtMap, jlbjlt.net and UMA: You Make Art