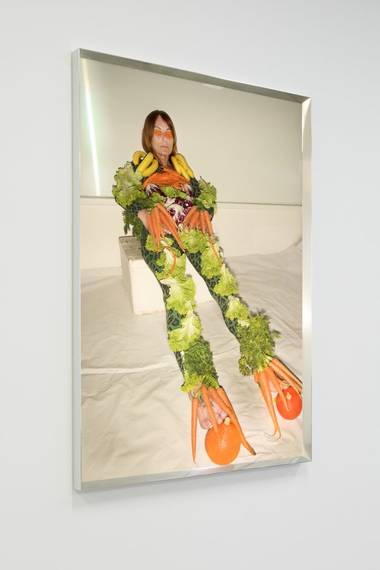

Daniela & Linda Dostálková: Campaign

10. 5. – 16. 6. 2019

opening: 9. 5. 2019

curator: Edith Jeřábková

An Interview with Daniela and Linda Dostálková

Most people are aware that the animal welfare movement is linked to feminism. But for a lot of people this conjures up vague ideas of sentimental women, often without a partner or children, advanced in years, who keep pets at home and walk to the park to feed the cats and pigeons. What objectives did you set yourselves in the project for the Cursor Gallery? Were you interested in questions of sentiment and how it might be functional? Or empathy in relation to animal rights? Do you agree with Peter Singer that animal rights is a separate issue from a “female” love of pets and from the emotive content of activist animal welfare campaigns?

DD: Our project for the Cursor Gallery is the outcome of the many years we have spent exploring the strategies pursued by animal rights groups. We were initially alerted to the theme by the 2005 film Our Daily Bread by Nikolaus Geyrhalter[1]. The film abstains from voiceover and uses simply images to chronicle the technological processes of industrial livestock production.

LD: We used Facebook purely as a research tool. We followed a range of activist organisations and downloaded clips of campaigns and events of everything from the Animal Liberation Front to farm animal sanctuaries. It was a desperately sad time and I admit that after two years I had to reduce my exposure. We made some of our research available via an internal lecture. The photographs of ALF activists wearing balaclavas and carrying beagle puppies from a laboratory in their arms caused great amusement. We realised that the way an organisation communicates its activities is crucial. We felt it was an area that touched us deeply and that it would be worth spending time on it.

DD: We’re concerned by what form activism should take these days, since it has to reflect its times in some way. Not everyone is able or willing to operate on the very boundaries of what is deemed legal, and we reckon that everyone can find a mode of activism that suits the kind of person they are.

LD: It’s very short-sighted to see women who adopt aging animals as irrational and sentimental. The last time we were in Warsaw we saw an old women with an Alsatian. At the same time as taking it for a walk, she was also feeding a flock of crows, which waited patiently for her and then accompanied her for several hundred metres to the park. It was an incredible sight. We wanted to film it, but then the question arose as to whether this method was the best way of communicating what we wanted to say through our work. In the end, isn’t this completely natural desire to care an example of the effective altruism Singer writes about?

DD: I wouldn’t underestimate women’s feelings for their pets. It’s a means of communication in its own right that creates a valuable bond with the animal. It’s not about simulation through the filter of animal “cuteness”, but a genuine interaction. In the video on display at the exhibition we collaborated with a trainer of Alsatians and Belgian Shepherds who made no secret of the fact that his dogs were fully subordinate to him. There is a woman we often meet in Grébovka Park in Prague, who has her third retired Alsatian and who is very critical of what she calls this narcissistic method of dog training. Ok, this is a topic for a different discussion. However, what we believe is that at present we have a very limited understanding of the coexistence of humankind and other species, and stereotypical ideas of lonely old women who look after tyrannised or ageing animals merely reinforces these prejudices. We believe that the figure of the “monstrous woman” acts as a powerful tool that reflects a fundamental female rhetoric. The Polish zoo-psychologist Simona Kossak (1943–2007) developed a rail jammer that prevented woodland creatures being killed by trains. In The Białowieza Forest Saga[2] she describes in detail her fascinating coexistence with wild animals against a historical backdrop and the development of Polish forestry. However, it’s not only women who communicate in a particular way with animals. A good example would be the male duo from the Gaia refuge in Spain.

Jacques Derrida wrote: “Monsters cannot be announced. One cannot say: ‘Here are our monsters’, without immediately turning the monsters into pets.”[3] From an intellectual perspective your project is based on a combination of a feminist theory of monsters and farm animal welfare. How was what was originally a human metaphor of a monster, the animalistic side of the monster, transferred from feminist theory to animals and the aesthetic of animal welfare activists? What we call “uncharismatic species”, i.e. creatures that find no favour with the general public and are therefore difficult to rescue and protect, might represent another, undomesticated nature, a wildness and ferocity. Who are these monsters and how do they operate?

LD: During a crisis, many species that are customarily portrayed as monsters appear in a new light, one that lies outside the notional hermeneutic circle. This helps us explain the conflict of extremes and involves a new type of logic. One of the key characteristics of a monster is its ability to attract and repel. This paradox reflects the human experience of nature in contemporary society. Monsters can help us put a name to that which is difficult to believe, and to domesticate (and thus absorb) that which we think is threatening us.

DD: The close associations between women, animals and monstrosity are often linked to romantic ideas and provide a very vital investigative resource of our communication. The stories recounted in novels contribute to the creation of a gender ideology that in our opinion is justified in the case of the protection of animal rights. Generally speaking, women are either marginalised or placed in a subsidiary role, whereas monstrous women in reality occupy the central position in their own stories. We avail ourselves of these positions even though the novel qua genre came into being primarily in order to promote the knightly virtues.

It would appear that you have long held a belief in metaphors and that you interrogate visual representation. Do you believe that contemporary society still knows how to read metaphors and relate critically to images?

LD: Recently, Daniela and I have begun to use a kind of para video format at exhibitions. For our own purposes we call it an anecdote. It’s basically what appears to be a sloppily composed video that combines shots we take on our mobiles and shots that look as though we’ve taken them on our mobiles even though we are meticulous in our selection of actors, costumes and mise-en-scène. The anecdote contains a joke, though not necessarily one that has you splitting your sides. Sometimes it’s more a lesson that may or may not apply to the viewer. It’s a kind of calibration device for the viewer.

Is your exhibition Campaign an image of a campaign or a campaign? Do you include any activist practices in your work?

LD: The title Campaign refers to the endeavour to win “someone” over to a cause and/or to its outcome. The title is intended to help display the background of a monster with an ambiguous identity that does not respect boundaries or accepted hierarchies, and provide space for the expression of domination and aggression, or, on the contrary, concern and care. As we see things, monsters are freely inspired by the way that activists strategise in an attempt to inform the general public of the practices of factory farming. These strategies, however well intended, themselves create monsters, because we remain unwilling to face up to reality as such. If a campaign is to be presented in some way, it must be preceded by the preparation of that which is to be looked down on. And we consciously work with these metaphors and while creating them are aware how complex, difficult to grasp and fragile this context is.

DD: Our work is reminiscent of what’s called biomimic marketing, i.e. the utilisation of an image of nature in order to create a product. In our hands the logic is inverted somewhat, since one of the “products” of this exhibition are feeding troughs that are set at a height that makes them suitable for human beings and not animals.

What I love about your work is the adventure involved in following how themes that we might well share are transformed into art forms, and how they permeate all the strata of the artwork including the aesthetic, which glitters on the surface for a moment before sinking deep inside. I also love the way you have theoretical assumptions appear for a moment before cutting them off and allowing popular or, indeed, unpopular emotions, tastes, styles or depictions of reality predominate. Your approach is critical, but then you switch off the criticism and have it defect to the other side. This also makes it exceedingly difficult to analyse your work, which takes it upon itself to show how contradictory reality is and how foolish it would be to attempt to capture it using only a single method. Nevertheless, your exhibition consists of several components that, it seems to me, have their own logic within the whole and differ in respect of the medium used. Could you say something about these?

DD: To be honest, we’re not too keen on describing individual parts of an exhibition. What’s important for us is the overall impression. In group exhibitions we often have a problem exhibiting a derivative, i.e. a single work, because it tends to be a kind of commentary on something else, an integral part of a whole. So we’re not big fans of accompanying programmes and private views and guided tours, because they disrupt the carefully constructed balance. Our endeavour to find a holistic approach sees us forever wondering what connections should be communicated and what should be more intuitive and hence difficult to communicate. Here the collaboration with the curator is crucial.

LD: Our father worked for a long time in the food industry. He often took us to work, where we had the opportunity to see food products being made. We also spent several summer holidays in the almond orchards in South Moravia. Later on our father was very involved in their preservation. I remember how, during the nineties, his job involved developing an exotically flavoured jam and introducing it onto the market. Even as children we understood that the product basically contained no fruit. It was a combination of sugar, gelatine, concentrates, and the dried stone pulp of a kiwi. However, for the sake of an ideally artificial flavour he travelled to several factories in Scandinavia. These days there’s a word for this: frankenfood. Perhaps this is where our fascination with monsters comes from.

That leads me on to one of your previous projects, the exhibition Heroic vs. Holistic (2017). Here already we see the theme of the exhibition emerging in a social metaphor revolving around the identity of a sour grape amongst the sweet, and you yourselves have given a name to this interpenetrative sphere of ethics and aesthetics in two concepts – the heroic and holistic, the industrial and post-industrial, or the patriarchal and post-humanist. Would you like to say a word about the links between these two works or tell us of other projects that, for instance, two years ago highlighted the issue of environmental grief, a subject that is only now appearing on the Czech art scene?

DD: Post-humanist questions pertaining to the depiction and protection of species are characteristic of our work. As you say, we first examined this theme in the exhibition Heroic vs. Holistic, which took the form of an erotic eco-drama. It was a group exhibition involving Barbara Falender, Grzegorz Kowalski, Miyeon Lee and Beny Wagner. We curated it at PLATO, in the former premises of a textiles shop. We prepared a series of video commentaries shot on the Greek island of Nisyros, where we had been invited by the organisation Are, at which the curator Nadja Argyropoulou assumed the role of an apparition as she called it. What we call environmental grief, i.e. the emotional distress of ecological workers, was the central theme of the video installation Acid Rain & The Labours of Hercules: Capture Slay Obtain Steel (2017). Another video entitled Invasive Species (2018), which had its première at the Cursor Gallery as part of the previous series of exhibitions Conditions of Impossibility curated by Václav Magid, made reference to the universal idea of the equality of all species. Last year, we published a book with the London publishing company InOtherWords entitled Hysteric Glamour, which was about the need for an authentic understanding of how we care for nature, which is crying out for our attention. The book was exhibited last year in our solo exhibition We Are Still the Same and You Are Always More, which took place at the Fotograf Gallery and was curated by Jiří Ptáček.

LD: For us the format of a book is a parallel artistic statement. We didn’t think of this book as if it were a catalogue accompanying the real work, but as an independent work with its own unique place within the installation in the broadest sense of the word. We have started work on a new book that is due to be released at the end of the year and will be called Survival Strategies for Contrasting Species. It will offer an interpretation of the visual identities of selected animal rights groups. Given their diverse programmes and ways of communicating with the public, we want to offer an artistic variation on their existing visual campaigns, which we would then make available to them for future utilisation.

DD: For us this represents a shift away from the originally conceived close cooperation with specific activists on the conception and realisation of their campaigns, to a more universal template that can then be freely applied in practice.

[1] Nikolaus Geyrhalter, Unser täglich Brot, Austria / Germany 2005, 92 min.

[2] Simona Kossak, Saga Puszczy Białowieza, Marginesy 2016.

[3] Jacques Derrida, “Some Statements and Truisms about Neologisms, Newisms, Postisms, Parasitisms, and Other Small Seismisms”, The States of Theory, ed. David Carroll, New York: Columbia University Press, 1989. 63–94, here: 80 http://hydra.humanities.uci.edu/derrida/jd.html

The exhibition programme of the Center for Contemporary Arts Prague receives support from the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic, Prague City Council, State Fund of Culture of the Czech Republic, City District Prague 7

Partners: Kostka stav

Media support: ArtMap, jlbjlt.net and UMA: You Make Art