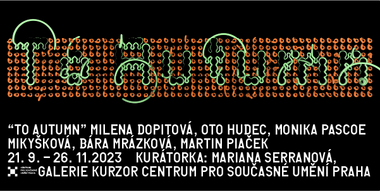

To Autumn

21. 9. 2023 – 26. 11. 2023

opening: 20. 9. 2023 from 6 pm

artists: Milena Dopitová, Oto Hudec,

Monika Pascoe Mikyšková, Bára Mrázková,

Martin Piaček

curator: Mariana Serranová

I. To Autumn

Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness,

Close bosom-friend of the maturing sun;

Conspiring with him how to load and bless

With fruit the vines that round the thatch-eves run;

(…)

John Keats, To Autumn (1819)

Listy se vzpřimují, svinují, hnědnou,

na rubu mají černé puchýře,

jsou mírně skleslé, černé polštářky

zahnívají a zůstávají viset.

Prstence, čárky nebo mozaiky

na listech, které hákovitě duří;

čepele listů s karmínovým lemem

a jejich žilky černé vodnaté.

(…)

Petr Borkovec, Podzim / Sonet

The leaves are springing up, curling, turning brown,

black blisters on the reverse,

slightly shrivelled, black pads

rot and remain hanging.

Rings, lines or mosaics

on the leaves, which glow hook-like;

leaf blades with crimson edging

and their veins black and watery.

(…)

Petr Borkovec, Autumn / Sonnet

“It’s nice, but the canals already smell like autumn.”

Věra Jirousová, October 1962

The part of life

devoted to contemplation

was at odds with the part

committed to action

(…)

Louise Glück, Autumn

Autumn time in the northern hemisphere. Like last year, this summer has broken temperature records planet-wide. The globe got beneath our skin. Our cycles between the 50th and 48th parallel north have specific qualities in nature and society. After the vegetative peak everything tends to gravitate back to earth, processes of thawing, a meditative looking back over previous seasons, often at odds with a return to active life.

The exhibition cycle Seasons has so far presented eleven Czech and Slovak artists, and will continue in this spirit. Given the intensified effects of globalisation, the similarity of climate, cultural traditions and geopolitical affiliations seemed a suitable key for the selection of artists. However, the climate of one country cannot be removed from the global context. Tracking domestic weather developments in light of the unpredictability of new climatic phenomena on a global scale is our new normal.

The exhibition Spring and All opened the cycle with W. C. Williams’ century-old poem of the same title, suggesting a pre-spring rawness, laying bare the materiality of this world, its coarseness and tenderness. The follow-up exhibition Another Summer accentuated the moment of repetition, cyclicality and fluidity. Temperature measurement strategies and the unpredictability of natural disasters came to the fore. The current exhibition To Autumn also traces human activity and its effects, suggesting the consequences of post-industrial times, the human-driven movement of materials and the impacts of the technology that controls us. We want to perceive the archetypal symbolism of the season through the prism of the possibilities of an existential, sensual and physical experience of nature in a time of climate crisis. Does not the decadence of autumn, at a time of the necessary evaluation of European values, add another layer? Is not the natural amplification of the perception of gravity and organic decay a reminder of the aging of our civilisation and our mortality?

II. To Earth

“The fractal face of the earth reveals itself as fragile, often ravaged. The earth turns its ravaged visage towards the sky; all manner of populations, armies, industry, tourism and invasions, have changed it into a valley of tears. Pillaged by those who pass but do not stay, its ruins are all we see. All we have before us are the remnants of a waste land, we live amongst memories.”

(Michel Serres, The Five Senses)

“What used to be the exclusive knowledge of a spiritual nature inseparable from mystical, poetic or other creative experience and thus guaranteed by the difficulty and necessary discipline of the path has become a general, trivial and seemingly worthless knowledge, an appropriated certainty for everyone. However, this fact is accepted as a preliminary level of convention by artists developing a new cultural coding out of respect and reverence for Planet Earth. In their work, they encounter nature as a being, forming a planetary body of which they feel part.” (Věra Jirousová, Zemi, 1993)

In 1993, in the introductory text to the group exhibition Zemi, Věra Jirousová drew attention to the “emerging planetary consciousness”. Three decades later, this is still relevant. In the meantime globalisation has reached its peak and our awareness of the environmental crisis has deepened. The “planetary body” resonates with Donna Haraway’s now oft-quoted thesis regarding the entanglement of living and non-living nature, or the concept of Gaia associated with James Lovelock and Bruno Latour. It is also clearly related to Rosi Braidotti’s description of the contemporary post-anthropocentric dynamic of “becoming-earth”, which implies an engaged collective belonging to the organism of the Earth.

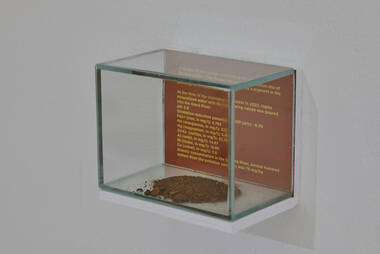

The discussion also relates to industry and mining and is part of the descriptions of the dislocation of raw materials, energy and labour. For example, a mineral is extracted from the ground, then processed in condensers. It travels around the globe from one production facility to another before becoming the final, commodifiable product. Uprooting within the agricultural sphere is even more illustrative of the same dynamic and is another theme of post-anthropocentric criticism. Agricultural crops are often harvested by seasonal labourers with no relationship with the land being cultivated. These alienating and colonising practices can be found in virtually all spheres of the globalised world and relate to mining, energy resources, and consumer industry and food chains. The energy crisis is also tangibly inscribed in our lives at the level of consumption. A dependence on oil and natural gas and on their extraction and supply. However, the debate relates mainly to what will or may happen.

However, the motivation behind the project Seasons was not to illustrate dystopian ideas regarding the future of the planet. While the start of the series included references to Octavia E. Butler’s catastrophic fiction in Parable of the Sower (1993), the aim was not to evoke extreme images, but to draw attention to a number of writers who, as far back as the last century, had engaged with the future through theory, fiction and poetry, and acknowledged the possibility of catastrophic development. The outcomes of the work of climatologists, hydrologists and environmentalists were taken seriously by writers like Butler at a time when the ecological crisis had not yet entered the public consciousness to the extent it has in the last decade.

III. Becoming

“Who is watching, who is even supposed to be watching. Human stories and their makeshift dwellings. The body. Whence it all pours. Greenhouse temptations, fragile as lettuce leaves, green as the moving screens of pine needles.”

Věra Jirousová, Landscape Before a Storm

digital watches.

without dial

no minute hand, no hour hand,

no eyes, no nose, no ears

deaf, constant landslides, 1, 2, 3…

1234567890123…

the future glacier now fills

all the valleys of the world with scratches of digits

wrapping around the wrist of the upright, Number Man

strange, shiny, black scratches

(…)

(Nanao Sakaki, Watch, Shinono, Autumn Equinox 1982)

…what the living eye cannot see is sleepless

chemistry in tanks

full on sleepless

(…)

Watch through the smokescreen, in the zenith

it’s a lost cause

/dural, kovral, scabies/ and in the sun

bath: pink dynasties of pink

Petr Kabeš, Deferral of the Landscape, 1970

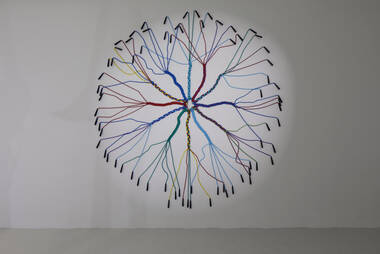

People don’t know what they are but have a certain idea of what they would like to become. But are they in control of what they are really becoming? A characteristic aspect of this problem is the relationship of man and machine. The cyborg as archetype of the post-industrial age into which we were born. Technology is no longer controlled by man: on the contrary, programmed machinery controls the course of society and the lives of individuals. New global information and financial networks not only deepen class differences, but participate in the construction of new identities, changing the politics of the body. On the one side stand machines, and on the other vulnerable bodies during times of pandemics and natural disasters. Inasmuch as “becoming a machine” is one of the vectors of the contemporary over-technicised world, then hybrid beings at the intersection of man and beast, so present in the contemporary imagination, are a metaphor for the complex relations between humans and living nature, an embodiment of the unbalanced relationship between human and animal. Rosi Braidotti describes the body as the complex interface of various social and symbolic tendencies: “[…] not an essence, let alone a biological substance, but a play of forces, a surface of intensities, pure simulacra without originals”. In the face of the quest for common survival, Donna Haraway also calls for a new hybrid imagery and for modes of representation that accentuate the common survival of diverse species. The creative practice and way of thinking infected with posthumanist scepticism also undergoes a certain hybridisation.

There is no universal key to how an engaged minority, consumer, citizen, artist, curator of contemporary art can creatively confront the contemporary crisis, how nature lovers, advocates for human, animal and plant rights – in short, contemporaries who recognise the intelligence of original ecosystems as we know them from childhood, storytelling, natural histories and documentaries – might contribute. From the start of this project I felt that a return to the aesthetics of nature within the context of its destruction made sense. The aim of the exhibitions was not to arouse nostalgia or stress traditional artistic practices, but to acknowledge the power of nature in its imagery, colours and intense energies, and to place its perfect organisation within the context of the crisis of an over-technologised world whose biochemical nature is changing due to human activities.

Marinana Serranová

(transl. Phil Jones)

The program of the Cursor Gallery is possible through kind support of Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic, Prague City Council, State Fund of Culture of the Czech Republic, City District Prague 7,

GESTOR – The Union for the Protection of Authorship

Partners: Kostka stav

Thanks: Joinmusic, Jiri Svestka Gallery

Media partners: ArtMap, jlbjlt.net and artalk.cz