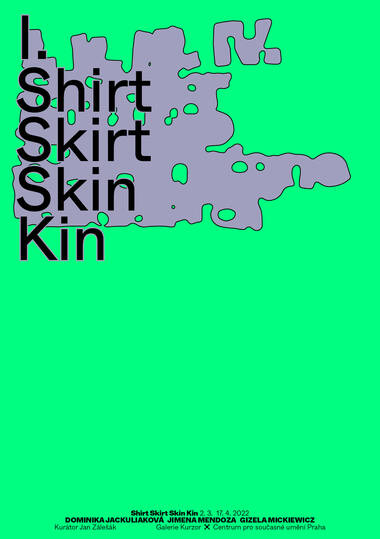

Shirt Skirt Skin Kin

Dominika Jackuliaková, Jimena Mendoza,

Gizela Mickiewicz

2. 3. 2022 – 17. 4. 2022

opening: 1. 3. 2022 from 6 pm

a guided tour with Jan Zálešák and

Dominika Jackuliaková: 24. 3. 2022 from 5 pm

a guided tour with Jan Zálešák and

Jimena Mendoza: 14. 4. 2022 from 6 pm

curator: Jan Zálešák

Preamble

A few days after the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, I was wondering how I would write the accompanying text to this exhibition – how I would organise the exhibition, how I would do anything at all (in the fashion I’ve been accustomed to doing it up till now). Now, as I read the sentences written a few weeks ago for Artmap and look around the gallery, it occurs to me that something of what we are experiencing with such intensity at this juncture in time is actually always with us. It’s just that it doesn’t usually cross the threshold of awareness. I don’t wish so much as to imply that there are any direct links to the conflict. But it is hard to ignore the fact that we begin the next curated cycle of exhibitions at the Cursor Gallery under conditions that affect us all on an existential level, similarly to the way that Václav Janoščík’s residency found itself on collision course with a global pandemic two years ago. I have no doubt that back then, too, the question arose of whether it made sense, whether art and the creation of exhibitions should not be put on the backburner so as to free up space for something more urgent. One could argue that the exhibitions of 2020, a year during which we had to rethink the meaning and content of concepts like proximity and mutuality, represented a kind of response. Today the situation is different. Nevertheless, I still believe we should find a response to it.

Shirt skirt skin kin

The four words in the title offer a pointer, an incentive to enter. Though at first sight the exhibition might appear to be a mélange of unrelated, or at least formally diverse elements, several motifs reappear, and I would like to focus on these here. Clothing (shirt, skirt) is one such theme. And immediately we might pause for a moment and offer a possible interpretation, one that transcends the framework of individual works and searches for the intersections between them, allowing itself to be carried away by their mutual proximity as it is transformed into kinship.

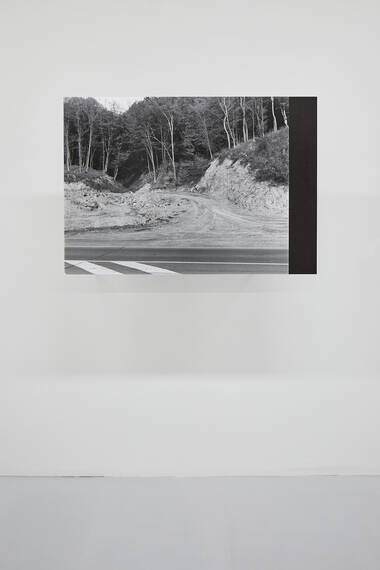

Unfinished Dress (2021) is an image from the series R2, in which Dominika Jackuliaková records landscape and human settlements marked by the construction of the expressway of the same name. This “southern motorway”, the current form of which was planned back in the 1990s, holds out the promise of acceleration and the elimination or at least the contraction of distance as one aspect of modernisation. The expressway is intended not only to connect Eastern and Western Slovakia and facilitate and speed up the movement of people and goods on this important axis, but also offer the inhabitants of neighbouring regions easier connection with the world. The section of highway currently under construction is in the Novohrad region, the name of which (from the Slavic Novgrad meaning New Castle) retains traces of the history of this part of Slovakia from when it was part of the Kingdom of Hungary.

It was here that the photographs were taken of three pieces of fabric featuring a “Hawaiian” motif – unfinished summer blouses made according to a pattern published in the magazine Burda. A more comprehensive reading of the image presupposes a certain cultural preambulation. The viewer is ideally able to identify or at least intuit that this is a pattern typical of the 1990s, and is aware of how DIY tailoring prefigured the as yet undeveloped fast-fashion market, which in turn went on to virtually wipe out the older cultural practice. Yet another clue is provided by the image’s place within the photographic series as a whole, in which Jackuliaková records the buildings and their interiors with the same fascination as the landscape scarred by the road construction work. In the vicinity of shots capturing slopes “stripped bare” of their top soil and remodelled with grit, trees “barbered” according to the course of power lines, or the “patterns” drawn on the large sheets of plywood used for casting smooth concrete surfaces, a space is opened up for another reading of Unfinished Dress, in which the hierarchy between the cultural and the natural is significantly weakened. People, fabrics, trees and slopes are all ultimately subject to similar abstract forces.

The ability of clothing to evoke, even in embryonic form, a strong affective reaction ultimately stems from a phenomenal, embodied experience, in which skin is activated as the boundary and point of transition between subject and object, inside and out. Of course, the significance of a garment is not limited to its protective function; it is not merely another layer of skin that we place between ourselves and that which we are no longer. It also carries cultural significance, hence its role and place in all kind of rituals both profane and magical. In the cosmogenic imagination it is not uncommon to believe a meadow or forest to be the skin or clothing of Earth, a green organic outer layer, beneath which is hidden the dark planet and everything animate and inanimate in it.

Jimena Mendoza ringed the gallery space with a strip of canvas featuring three painted stripes and a buckle. By means of an almost scenographic, site-specific gesture, Mendoza transformed the entire space not into a stage, but into a body. The placing of the work in space and its title – Cuerpo I, (2022) – opens up the space for an ambivalent, ambiguous reading. Are we inside a body, one of its cavities? Or does it surround us? The canvas belt that encircles the space without any break, such that if we want to proceed further we must cross a small footbridge, activates an experience of our own corporeality, while at the same time opening up a relationship to another, inhuman body made of bricks and plaster, columns and floor. The evocation of the “corporeal” quality of place raises the question of what happens when the gallery is empty, or more precisely, when it is devoid of people.

Cuerpo I (which we could loosely translate as “corpus” or “body”) literally confronts us with the possibility of a relationality that is not restricted to interpersonal communication or interaction. The ambivalence of remaining in one’s own body while being aware of its incorporation into a network of relationships that transcend the plane of interpersonal communication is a suitable starting point for an encounter with the latest work of Gizela Mickiewicz. Gestures From Afar (2022) is set within the perfect ambivalence of the physical and the non-physical. The sculpture, which is completed with a hand gesture modeled on the artist’s own palm, represents the affective agency of the human body, an “instinctive” or reflexive reaction to a sensory stimulus. The human gesture, which has fascinated Mickiewicz in recent years, relates to events it cannot in reality influence and which we can only be aware of in retrospect. The undulation in which the shape of the forearm is repeated and replicated recedes from the image of the human body and opens up a series of associations in which no small role is played by the content of our unconscious. At the same time, however, despite all the “inhumanity” further accentuated on the level of texture beneath the smooth semi-transparent surface of which tiny perlite crystals are pressed together, the sculpture is inevitably anthropomorphic. This is not only because of the clenched hand, but also the polychromy that suggests the colour of bruising. We are thus witness to the fusion of a very abstract idea evoking the capacity of sympathetic magic to act indirectly on things beyond reach, and a radically material image of the body, of which we appear to have a subcutaneous image that contrasts strongly with the marble-white purity of the torso (Holding Off States of Weakness, 2021) originating from the artist’s previous cycle.

Kinship

While a helping hand, a plan, an arrow indicating the direction of a tour can assist, it can also act as an obstacle placed before an individual viewer’s appreciation. I am well aware of this fact, but in the end conceived of the text as a guide to interpreting the works on show. At the same time, I try to draw attention to the fact that within the framework of a group exhibition meaning is also inevitably situated and formed, inter alia, by kinship (with the artist’s work as a whole, of which we see only an example at an exhibition), as well as through the opening up of the possibility of encounters with the other right here and now. Over the course of the upcoming year at the Cursor Gallery, the plan is that the story does not end here. Instead, we will continue in the company of other exhibitors to try to find vibrant links and connections to work that has already been, or is due to be, exhibited in the gallery. We will attempt to build up gradually a dense network of contacts and relationships spreading across the cycle as a whole, which has now begun to take shape in the form of this current exhibition.

Dominika Jackuliaková works with photography, specifically with analogue techniques, using which she creates images of cultural landscapes and found still lifes. She lives and works in Bratislava, but regularly returns to her hometown of Lučenec. The themes of her work are inseparable from her frequent travels, whether between the cities referred to, or between Slovakia and the United States, where part of her family lives.

Gizela Mickiewicz works with sculpture, object, installation and drawing. She has long been fascinated by objects, materials and the relationships between them, unburdened by the necessity to transmit messages directly to the viewer. However, in recent years an explicit image of the human figure has acquired more emphasis, and the entirety of her work can be seen as expressing an ambivalent humanism. She lives and works in Warsaw, where she collaborates with the Gallery Stereo.

Jimena Mendoza creates art situated at the intersection of craft and design. She works mainly with ceramics, glass, drawings and collages, which she combines into complex installations. She draws on non-Western and pre-Columbian iconography, though ultimately she tends toward an idiosyncrasy based on an intense interest in selected aspects of the (visual) culture of Central and Eastern Europe. She is from Mexico, but lives and works in Prague.

The exhibition was supported by Polish Institute in Prague and Adam Mickiewicz Institute.

The program of the Cursor Gallery is possible through kind support of Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic, Prague City Council, State Fund of Culture of the Czech Republic, City District Prague 7, GESTOR – The Union for the Protection of Authorship

Partners: Kostka stav

Media partners: ArtMap, jlbjlt.net, Náš REGION

and Mladý svět and UMA: You Make Art