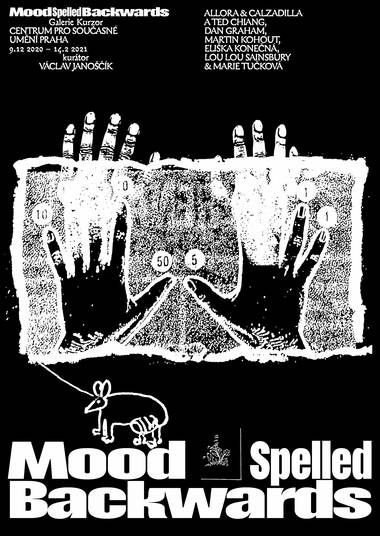

Mood Spelled Backwards

9. 12. 2020 – 14. 2. 2021

Allora & Calzadilla and Ted Chiang, Dan Graham, Martin Kohout, Eliška Konečná, Lou Lou Sainsbury & Marie Tučková

installation in the courtyard area: Michal Č. Šembera

curator: Václav Janoščík

Download the exhibition brochure here

Chapter One

Each of us has our places, desires and histories

“My Body May Be Present

But My Soul Is On The Beach.

I am already dead.”

Death Stranding, Hideo Kojima

At some point in the past there was a moment when each of us came into contact with music. It ceased to be simply noise emanating from a radio, the backdrop to our childhood, and began to shape the contours of our perception of the world, our expectations of the future, and our very identities. Such a moment is usually associated with adolescence, rebelliousness, the need to find one’s own place and stand out from the crowd. For me, on the contrary, it was more about a timid search for a sense of togetherness and the possibility of sharing a nagging feeling of not belonging anywhere.

During the 2000s, as I made my way through secondary school, found jobs in factories and construction sites or on the Kamencové Lake in Chomutov, I also discovered the former Evropa cinema, at that time already in ruins, which enthusiasts and friends were turning into a social, cultural and ecological centre with their own hands. In between weekend clear-outs, raising money and the organisation of many other activities, in amongst the scraps of the old projection screen, the glass wool falling from the ceiling, and chairs ripped from the auditorium, there were also concerts. Unknown bands from the neighbouring prefab houses and even neighbouring countries came here more in order to meet and fill the huge space with the vibrations of unidentifiable instruments connected to the speaker system.

At that time I understood almost nothing. I didn’t understand why there was a war going on in Iraq, why people whose lives involved travelling between industrial zones and prefab apartment blocks would vote for the rightwing Civic Democratic Party, what emo was, and why everyone was wearing hip-huggers or cargo pants. Above all I didn’t understand myself. I might not understand the marathons of industrial music taking place at the Evropa cinema, but at least everything else made sense here. The momentary intersection of worlds and vibrations convinced me that everything could be different.

In the end the city didn’t give the go-ahead to the planned refurbishment of the cinema, and today there is a sprawling car park where it used to stand. A space drenched in beer, outsiderness, unidentifiable anger, euphoria and failure remained a virtual space for me, a ravetopia of real, incredible freedom.

Chapter Two

… but sharing is far more important

“I can do anything

I can be what you tell me to be

I can be what you need

I can be your real life sugar

I can live in your dreams

Will you be my fantasy?”

Yves Tumor, Kerosene!

We tend to view our past as a set of events, wars or revolutions. We perceive the present in a similar way, through an inexorable flow of information, messages and images. Eventually even the future starts to appear both strangely crowded and empty at the same time; increasingly calculable (data, models, trends) and yet uncertain (from ecological issues to growing nationalist and xenophobic tendencies).

However, our entwinement within different times is infinitely more complex. What if we were to perceive emotions and affects rather than news, forms of social energy rather than individual headlines and affairs? The past would then seem like a reservoir of different situations and moods, the present would not simply be a punctual “here and now”, but also – and more importantly – a contraction of differently expansive goals and visions that would actively intervene in the future, itself now a shared pool of possibilities and objectives. Many people would rather have their own private Jacuzzi, though maybe you yourself are aware of the need to share, the need for tolerance of other bodies, narratives and cultures.

It is in this respect that music is important. We do not only have to listen to it, but can subject it to comparison, context, doubts and criticism. It can characterise social moods, but also suppressed tensions, not only hackneyed clichés, but also conflict and the possibility of misunderstanding. And so music of the sixties is associated with political visions and protests, while punk emerged in the seventies as a reaction to their collapse. Techno and rave arose at the turn of the eighties and nineties as a scream echoing within deepening social chasms. The 2000s saw the arrival of emo’s generational resistance, which ten years earlier had been represented by grunge and Nirvana. In the 2010s we witnessed the invasion of depression and psychopharmaca in xanax rap and other genres.

Far more intimate connections, images and narratives can be discerned in music, its environment and listener communities.

Chapter Three

An ontology of music, the politics of emotion, dictatorship of happiness

“We work hard, play hard

Keep partyin' like it's your job”

Play Hard, David Guetta

The power of music resides in how it transforms our world and manipulates time and space. Whether this involve the abstract landscapes of Vangelis, the airport halls of Brian Eno, the streams of fluids and love of Jenny Hval, a scrolling through the sonic worlds of Oneohtrix Point Never, or the apocalyptic views of James Ferraro... music can lift us and change us. This is what affectivity means. It’s not just about emotions, but much more about transformation and the connections taking place between me and the environment. If I’m really struck by some music, a computer game, a landscape or a person, I cannot separate them from me. What of all of this is me, and what are all the things you, nature, patterns of behaviour or rhythms represent?

It is no coincidence that the environment of a music club is bound up with many emancipation movements. Whether this involve the Afro-American civil rights movement, the LGBTQ+ community, or the British working class, clubs created space for freedom, frustration and the experience of sharing and collectivism. However, club music was to find its way into mainstream and pop. Club music and its characteristic features (breaks and drops, connections forged through movement, and a game played with musical chance) have become ubiquitous and empty, from Calvin Harris via Lady Gaga all the way to David Guetta.

“We work hard, play hard / Keep partyin' like it's your job." While it used to be politics that found its way into club music, these days it is pop and club music that are getting into politics. Clubbing seems to have become a lifestyle accessory, one aspect of the neoliberal requirement to have fun. The very categories of happiness, meetings, sharing or attunement are fused into fun, party and mood.

If we want to return to our ability to experience not only pleasure, but also shared happiness, if we do not want to remain tethered to pleasure and popularity, but to speak of the possibilities of culture and art, then we must also return to music. This does not simply involve using music’s forms, rhythms or clips, but working with the dynamics, affectivity, con-figuration and refrain of our expectations and with the polyphony of our desire.

Chapter Four

How desirous are you?

“He’s too stoned to be president.”

Dan Graham, Don't Trust Anyone Over 30

Dan Graham’s video, performance and puppet show Don't Trust Anyone Over 30 takes place between the sixties and seventies and takes this return to the interconnectedness between music and politics as seriously as is humanly possible. Would it be possible to give LSD to all MPs, to govern on the basis of astrology, to reduce the voting age to 14 and to elect a rock ‘n roll singer as president? And then to remove him with his own consent?

“Don’t trust anyone over ten” ends Graham’s rock ‘n roll puppet show, which shifts our political and personal aspirations into an uncomfortably strong historical and generational framework. What does music offer us and what does it efface? Which struggles are ours and which relate to others? All possible protests were here, yet still there is time for new ones.

The music video by Marie Tučková and Lou Lou Sainsbury also adopts a generational yet more contemporary perspective. Their song, story, chorale, their gradually cultivated repetition, also works with rhythm, not only musical, but with the tempo of human life and perception. Objects, relationships, intimacy, years and people get lost in the holes of a bedroom, perhaps the very room in which we all began to listen to the music that ceased to be merely the soundtrack of the times and the mantra of adults, but mysteriously captured our fears and hopes, gave us rhythm and energy.

The problem of music and listening turns into a question of place, time and identity. Who am I that I am able to follow all the government measures, reports of environmental disasters, and face the inability of humankind to confront evil? Who did I become as I became adult? Who am I able to be, contrary to my firm convictions or following their example? And what kind of music will accompany me?

Chapter Five

Possibilities and bodies

“Why am I so lost?

Why am I so lost?”

Holly Herndon, Crawler

What is the melody of our world? A boring refrain, the payment of taxes, business as usual, the reproduction of order must be balanced by soar, break and drop as in dance music. Succeeding or being happy is like jumping onto a podium. Showing initiative, being seen, setting the tempo, imposing rhythm or playing calmly out of tune... these are just some of the principles of neoliberal music.

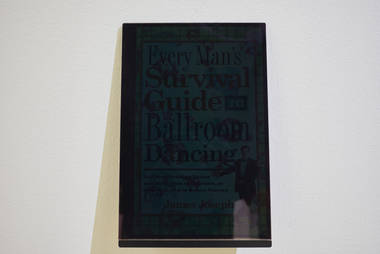

Martin Kohout is constantly focused on the conditions of possibility and their acceptance. Whether this be the internet, design, music or social organisation, he is pointing to the possibilities and impossibilities of that which we do or feel. In his series Survival Guides (for Ballroom Dancers, Renovators, Softball Moms, Working Parents and Troubled Folk in General) he shows very effectively how easily we create, accept and reproduce stereotypes according to our interests, parents or social status.

The relationship between music and the listener emerges once more, but this time round with a warning that I may be overestimating the political role of music, that I not impose a leftwing horizon of the future or protest culture on it. After all, we are talking the body and movement. And also survival.

Back on earth, in the auditorium, I am grounded by the objects, reliefs and con-figurations of Eliška Konečná. These do not comprise simply a body, image or projection screen, but open up space and landmarks, as well as proximity and tension. No longer being a sculpture, but becoming a sculpture. Not a painting, perhaps a folding screen. I like screens because not only do they reveal, but they conceal, they divide and compel movement.

Chapter Six

The great outdoors and the great silence

“We wanted it to be different

But that ain't happening any time soon

Mood spelled backwards

Says ‘doom’”

Oneohtrix Point Never, Babylon

Alex was a grey parrot who communicated with humans in the most complex fashion observed to date as part of a 30-year project conducted by the animal psychologist Irene Pepperberg. Or at least within the framework of our Western concept of communication and animals, nature and people. Alex learned how to use basic abstract concepts (larger, smaller, different, same...) and operations. He not only performed these actions, but occasionally made deliberate mistakes or became bored with the tasks set him. However, the more important question is: what did people learn?

Alex is the narrator and central character of the video by the duo Allora & Calzadilla created in collaboration with the sci-fi writer Ted Chiang. The title The Great Silence is a reference to Fermi’s paradox, namely, the discrepancy between the high probability of the existence of intelligent extraterrestrial life, and the absence of any signs of it. How is it that we devote so much energy to listening to the universe and its silence, and so little to listening to other inhabitants of our planet or even each other?

Music is constantly fading, there is a great silence between songs and even individual beats. As in a car park in the middle of a housing estate, or at seven in the morning when a party is over and people start returning somewhere, or as throughout the whole of the entire Milky Way, to which we listen carefully, or like answers to the questions of all these people failing to communicate and convey, respect and share. Today we are overwhelmed with so many messages, images and sounds, we entwine our lives around so many different rhythms that we are forced to concede that great silence. Without it we would have nothing to fill and to say.

The great planetary silence of the Anthropocene is filled by Alex’s final words: “You be good, I love you.”

Václav Janoščík

(transl. Phil Jones)

The programme of the Center for Contemporary Arts Prague receives support from the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic, Prague City Council, State Fund of Culture of the Czech Republic, City District

Prague 7

partners: Kostka stav

poděkování: Joinmusic

media support: ArtMap, jlbjlt.net and UMA: You Make Art