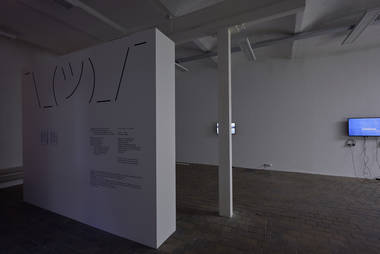

Conditions of Impossibility VII/VII: The Psychopathology of the Planet

December 19, 2018 – March 3, 2019

opening: December 18, 2018

guided tour with the curator: February 21, 2019

curator: Václav Magid

artists: András Cséfalvay, Aleš Čermák, Tereza Darmovzalová, Daniela & Linda Dostálková, Matěj Pavlík, Vojtěch Märc, Jan Kolský, Jiří Žák

Psychopathology of the Planet is the final part of a cycle of seven thematic exhibitions entitled Conditions of Impossibility. Since we are nearing completion, it might be worth reminding ourselves of the overall project objective defined at the outset. In the text accompanying the first exhibition we read that the cycle was to be a “comprehensive critical reflection upon the assumptions and frameworks that at present define the (im)possibility of knowledge, action and aesthetic experience”. The text continues: “Over the last few years there has been much talk of the turn to the object: in this cycle it is the subject that will be put under the spotlight. However, this subject is under assault and losing the ground from beneath its feet.” Eighteen months ago, when these words were written, the subject was still hiding behind objects and screaming loudly “I’m not here!”. At present, the subject is elbowing its way back to the forefront of things, as pure and innocent as a newborn baby, and flaunting the authenticity of the experience of its fleeting identity. However, its youth is decrepit and its newly discovered “honesty” ironic to the core. As recent events on the Czech art scene clearly show, the subject’s experience is framed by institutionalised anxiety and #suffering caused by the environmental and social impacts of consumerism.

The exhibitions making up the cycle Conditions of Impossibility have patiently profiled many of the aspects that characterise today’s typical subject as a complex, fragmented being. The subject remains trapped in a permanent present because it is no longer capable of experiencing time as a continuum within which it would be in a position to capitalise on past experience and map out the contours of possible futures (Loss of Time). It is forever moving between different environments, the comfort of which conceals the subject’s rootlessness, and is losing sight of the horizon of the common world, for which it should take and share responsibility jointly and severally along with other living creatures ([Im]mediate). In the never-ending process of work, which the subject regards as self-realisation, it experiences the most profound alienation of its entire personality, while in the struggle for the right to indolence and emancipation from work it drops from chronic fatigue (The Work of Indolence). Under the onslaught of relentless communication it is no longer able to discern the meaning of speech and is therefore increasingly subordinate to its performative power, which it is unable to resist because it would rather give up the word altogether than risk offending someone with it (Alogorrhea). The subject does not know what to do with its humanity upon being obliged to confront both the destructive whims of nature that has become excessively human, and a machine intelligence that eludes human control, while at the same time dealing with the dark stain of inhuman origin that has appeared in the light of its own reason (Inhuman Resources). It busies itself with minor practical issues so as to preserve the pleasure of free decision-making given that it no longer has anything to say regarding the objectives and values in accordance with which technology confronts and controls the world, including the subject itself (Technical Detail).

It doesn’t need emphasising that, during the course of this cycle of exhibitions, those who have participated have experienced the phenomena outlined above for themselves. And as with almost every long-term, demanding project requiring huge amounts of our creative energies, burnout inevitably ensues. Under the modern conditions of production it is considered somewhat infra dig to admit to tiredness or scepticism. One is expected instead to present one’s product with exaggerated enthusiasm and effervescence. However, let us rather admit to our burnout and ask what can be learned from this situation.

The term burnout is often used to describe one of the defining features of today’s society, which is primarily focused on performance (Byung-Chul Han). This performance is mediated by information and communication technologies operating at speeds no human could ever compete with (Franco Berardi). We respond to the tsunami of inputs by panicking, which subsequently becomes depression brought on by our inability to meet the demands being placed on us. The situation is all the more frustrating for the fact that the requirements we are unable to fulfil are ones we have placed upon ourselves. Since our performance is motivated above all by the ideal of self-realisation, we are not subject to external coercion, but to a pressure that comes from within. Unlike melancholy, which is normally regarded as an inability to come to terms with the loss of the object of desire, the depression being experienced by the modern subject is caused by an excess of such objects. The goal of our performance is supposed to be happiness. However, since the attempt to achieve it occupies all of our time and absorbs all of our strength, this happiness remains forever beyond our reach. On the contrary, the ongoing increase in productivity and competition intensifies our feelings of weariness, disappointment, sadness and bad faith. On the other hand, the effortless attainment of a myriad of the small pleasures offered by the consumer economy is equally duplicitous: the term “depressive hedonia” (coined by Mark Fisher) describes a subject that cannot stand still for one moment but must constantly enjoy something, whether this involve listening to music, watching videos, playing games, shopping or gorging on junk food. As soon as the flow of pleasures dries up, we become nervous and insecure. We don’t know what to do with ourselves, we don’t really know who we are.

Anxiety, panic, burnout and depression, along with many other psychological disorders, are spreading to such an extent that one is justified in speaking of an epidemic of mental disorders. This is not about individual failure or misfortune in life, but about the impact that economic, technological, social and environmental processes (the last sometimes called “environmental grief”) has on the individual. What this means is that, if we do not want only to treat symptoms but also deal with the underlying causes of these dysfunctions, we must “politicise” mental health. And as many thinkers attempting by means of an analysis of burnout, panic and depression to arrive at an overall reflection of today’s dominant ideology (at least one lost his life in the attempt) have pointed out, these states of mind have an upside. By not suppressing them immediately but instead observing them in order to understand them better, we can learn something fundamental about the conditions of life in modern society and how we should change them.

Perhaps, then, Berardi is right when he claims that depression as “the suspension of the sharing of time, as an awakening to a senseless world […] comes closes to truth”. If depression is a sense of the profound insignificance of our lives, then it is a state in which we are closest to what Eugene Thacker calls the “world-without-us” or Planet. If we take the word World as referring to the subjectively experienced “world-for-us”, and the word Earth as referring to the “world-in-itself” as an object of scientific description, then the “world-without-us” is simply one of the innumerable planets in the universe. If we speak of the Planet, then we have shifted to a cosmic scale that is completely indifferent to human values and objectives. The Planet as “world-without-us” is what we get when we remove the human and all human meaning from the world – and this is what happens to us in a state of depression. By this reckoning, Psychopathology of the Planet would be a paradoxical attempt to describe the possibilities of mental illness and mental health in a world without meaning.

Václav Magid

(transl. Phil Jones)

The exhibition programme of the Foundation and Center for Contemporary Arts Prague receives support from the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic, Prague City Council, State Fund of Culture of the Czech Republic, City District Prague 7

Media support: ArtMap, jlbjlt.net and UMA: You Make Art