Politik-um / New Engagement

15. 5. – 10. 6. 2002

exhibition space: Prague Castle, courtyard and Tereziánské křídlo Gallery

curators: Ludvík Hlaváček; Keiko Sei

exhibiting artists: Michael Bielický (ČR), Daniel Bozhkov (USA/Bulharsko), Jiří Černický (ČR), David Černý (ČR), Milena Dopitová (ČR), Harun Farocki (Německo), Cindy G. Flores (Mexiko), Ingo Günther (Německo), Fran Ilich (Mexiko), Sanja Iveković (Chorvatsko) Nada Dimic File, Zdena Kolečková (ČR), Jan J. Kotík (USA/ČR), Alena Kotzmannová (ČR), Beth Lazroe (USA), Adéla Matasová (ČR), Erbosyn Meldibekov (Kazakhstan), Michal Nesázal (ČR), Otto Placht (ČR), Pode Bal (ČR), Tamar Raban (Izrael), Julia Scher (USA), Silver (ČR), Zitta Sultanbaeyva Ablikim Akmullaev (Kazakhstan), Šťepánka Šimlová (ČR), Milica Tomić (Jugoslávie), Filip Turek (ČR), Martin Zet (ČR)

In the Czech Republic, a strong distaste towards the concept of "political art" prevails up until this day. This is understandable, when we take into account that under communism, political engagement, in the interest of the governing ideology, was forcibly demanded of artists. In a democratic society, artists concern themselves with public and political issues on their own choosing and become "engaged" for themselves and by themselves - as artists, citizens, and human beings. Developments in the art world, as well as in the political sphere, provide the stimulus for contemporary artists to engage themselves in public and political issues.

Art follows politics

Art has been, to a certain extent, political throughout most of its history; whether it was an expression of tribal magic, religious ideas, the social position of its patrons, or, as of the 19th century, an expression of democratic ideals. If, in the 19th and 20th centuries, the visual arts wandered through a dense undergrowth of solitary human souls, it was because the development of democracy itself has raised questions concerning the relationship between the individual's freedom and his dependence on others and on social institutions. Concerns about the social relationships of the individual have been an integral part of many art-movements, particularly in the second half of the 20th century, and it appears that artists' interest in social affairs has significantly increased over the recent years.

Contemporary politics provokes the engagement of artists

The political order continually refines its mode of conduct, as does art and a range of other social activities, which leads towards a progressive closing in on itself and a shift from concerns in human affairs to the mechanisms of management and control. In the endeavor to establish an effective political discourse, the questioning of one's own views, distancing oneself from the terms set by competing parties, and an unhindered look around at those things that bring joy to human life and give it reason, seem to have been excluded. Political art represents a spontaneous human endeavor to make an "public issue" a "human issue". Human decisions should not merely be a choice between the right and the left of the political spectrum, but decisions made vis-a-vis the inexhaustibly diverse, surprising and living reality.

What is political art?

In contemporary art textbooks, the concept of "political art" is most closely connected with the art of activists, who defend the rights of social minorities and assert the existence of alternative social models. Following the end of the Cold War and polarity of ideologies, the activist's polarization also seems to have become substituted by the individual artist's interest in a range of everyday social problems. Problems that result from living in a society controlled by consumerism and the emotionless control mechanisms that produce a concentration of power, unequal distribution of goods and resources, and lay the ground for hostile relations between people. Particularly in our country, where, for many years, there was no opportunity for natural development, the individual artists' views on political art are quite diverse.

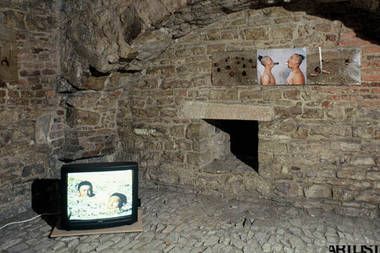

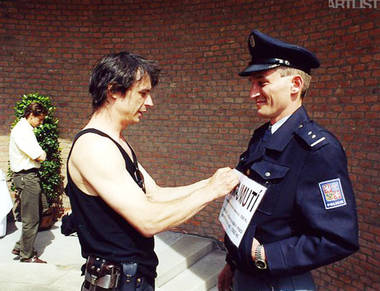

The projects from local artists, that have been brought together for this exhibition, present a broad range of engagement in artistic, civic and human affairs. Some artists comment on specific political events or situations that have become public issues through the attention of the media. Such is the case with the works of the artists Jiří Černicky, Jan J. Kotik, Martin Zet, Michael Bielicky and the artist group Podebal. The other projects actualize human activities, in which dangerous or sensitive elements are hidden, for example the development of technology as a means of controlling people's lives (Adela Matasová), or the underlying violence hidden in an innocent child's games (Alena Kotzmannová).

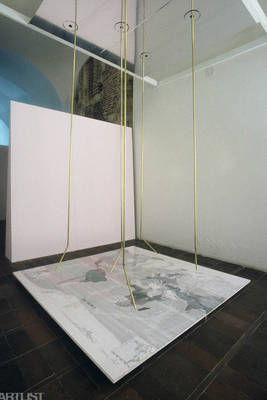

Michal Nesazal expresses in his landscapes - made in style of Barbie - his fear that the development of simulation techniques will increase the artificial character of our environment. Štěpánka Šimlová uses the possibilities of the computer to show that the beauty of the landscape and the cruelty of war are very close to one another. Otto Placht, with his project for a cultural center on Lake Yarina Cocha in the Peruvian Amazon, shows the closeness and distance of geographically removed cultures. The artist group Silver, known for their successful projects in field of digital techniques, refers to the limits of the technical means of human communication. Milena Dopitová understands the political content of artwork as a general reminder of human misery, illness and death. David Černy by his play-full work demythises the place and weep up a powder from the old stone.

Political art is weak and ineffective politics

Art is not interested in achieving anything. Certainly, every artist would like to be able to live off the fruits of their work, however - assuming they are artists - they are not willing to adapt their output to meet market demand. The artworks that they produce are not goal-driven, but merely an expression of what the artist feels to be important. Artists do not have to answer for their expression to a political party, however they know that, in their individual lives, they are dependent on other people and on social institutions. Each individual artwork presents an unverified, personally interested message that cannot avoid but to be one-sided. This, however, should not be regarded as a defect, since human society is, in itself, made up of imperfect individuals.

Impotence is an essential feature of art

Art can not seize political power. However, the art of Fascism and Communism have taught us that by relinquishing freedom, the artist provides the politician an extremely effective means of maintaining political power. As a functionary tool, art can gain political power, it then, however, ceases to be art.

Ludvík Hlaváček

Concerning the selection of artists and projects from other countries and continents

Political art or activism

Recently I was asked what was the difference between political art and activism. The question came out of a reflection about the recent trend of activism in art, as it has been seen in the projects of the artist group Podebal in this country. There is no clear common distinction between the two, and sometimes the names and works of the artists working in these spheres overlap.

I shall try, however, roughly to summarize what the differences are. The successful film of Ken Loach, "Bread and Roses", is a good starting point for looking at this question. The film is about a labor strike by Latino workers in California, who are largely exploited. The strike was inspired by an American union activist, who provided the strikers with different strategies of action and the slogan "We want Bread, but we want Roses, too", which was supposedly used during a textile workers strike in Lawrence, Massachusetts in 1912.

The film doesn't directly refer this event, and whether the slogan was really used in Lawrence or not, has been disputed by historians - the general consensus being that it, in fact, was not. The myth, however, has placed the Lawrence event in the public memory, and provided inspiration for later labor activists. Thus, the Lawrence strike has become the most famous event in the history of labor movement in the United States.

When an artist is engaged in making a political statement in their artwork, it probably serves in this myth-making role: to give evocation, story and memory to social and political problems and events that might otherwise be overlooked and forgotten. This is, in the larger picture, what political art does.

Activists, on the other hand, are more like strategy makers for actual situations. In the above-mentioned film, they are represented by two union activists who invent various strategies and techniques (breaking up corporate parties, etc.) for workers in order to get media attention and make their voices publicly heard.

Activists constantly monitor the "activities" of the "big guys" - such as corporations and governmental authorities - in order to create and invent tactics to make them aware that the "small guys" won't remain as ignorant and subordinate as they have been in the past, and are "supposed to be", and, simply to l et them know that: "We know what you are doing and we won't keep our mouths shut."

Their tactics and techniques have diversified over the decades as the citizens' consciousness grew and as new technology developed. We can usually see their activities on the Internet and, occasionally, we can see "fireworks", resulting from their actions, in various anti-globalization demonstrations. As their aim is to get the attention of the media and public, these actions have become more and more over the top; and this is what has caught the eye of the art world.

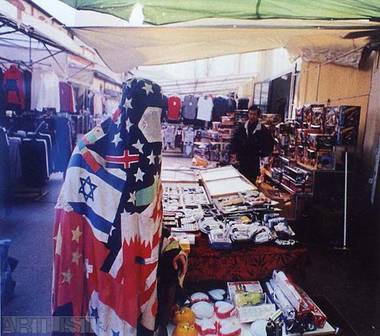

'Activism' has thus become an unignorable "calling the shot" item in art. The list of their methods is endless: hacking (chaos computer club), mimicking the structure and the design of the big guys (RTMark), mirroring (Mongrel), creating the virtual nation (Ingo Gunther' s Refugee Republic, NSK state, Virtual Yugoslavia), intercepting information transmission (Brian Springer's "SPIN", Marko Peljhan's Makrolab), and on and on....

New Engagement

For this exhibition at the Prague castle, we rounded up all these activities under the term of 'new engagement' (as it doesn't translate well into Czech, we use the English term, which sounds more neutral) in order to emphasize the fact that here are people with enough means, technology, or at least fantasy, who are saying farewell to the time when people were forced to politicize and engage their work in accordance to some higher authority's plan and policy. Based on this idea, we also invited artists and projects from "the outside" that could give light to various aspects of political art, as follows:

Awareness of our "monitored life" and how we can turn it into a "monitoring power" activity [Sher, Farocki]

Accessibility to information, technology and media [Farocki, Gunther]

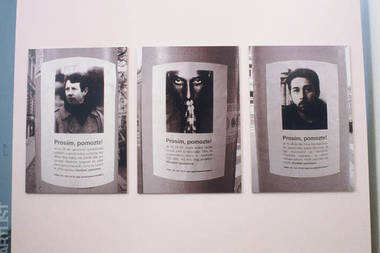

The potential of "the third power" (the emergence of new civic initiatives and NGOs, that have become a significant counterpart to governments and corporations) [refugees in the Gunther's project, women in the Ivekovic's project]

The problem of borders [Ilic's and Gunther's projects on borders between nations and Flores's project on borders between genders]

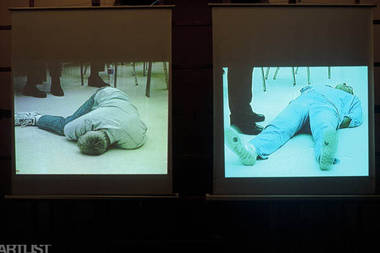

Rapid reaction force (I'd like to use the term, not in the conventional military sense, but in the sense of how an artist quickly reacts to a political event, and in this sense, the series of projects by Milica Tomic are a prominent example of the artists' reaction throughout the Yugoslavian crisis)

Performed engagement [Bozkov, Meldibekov, Sher]

I must explain more about the last "performed engagement". Because of the recent rapid rise of new media on the art scene, it seems to have dominated the use of technology in the sphere of political art and activism today. However, the basic idea of projects that use technology has been incorporated into artwork by performance artists for decades. At the same time, artists that use technology rely on the "performance" of the machines; therefore performance here has to be regarded in a wider perspective.

In the video of "Pol Pot" by Erbosyn Meldibekov from Kazakhstan, the audience will find the performance of the local people as actually the embodiment of the idea of autocracy, the very base of the Asian style of political power. The performance of Tamar Rabin, on the other hand, serves almost as a rite for her, allowing her to meet her fellow Palestinian artist who lives in Chevron, and hence, whom she cannot meet in her own country, although they live so close.

The women textile workers in Lawrence were successful, and their legacy remains in the phrase "Bread and Roses". The women textile workers in Croatia, in the project of Sanja Ivekovic "Nada Dimic", were deprived of their partisan hero's name, Nada Dimic, and finally even their jobs. The name of Nada Dimic, however, remains in people's minds through Ivekovic's project. And it is generating the action of people who care about the fired women workers. This is what political art does.

Keiko Sei

Organizer

Center for Contemporary Arts Prague, o.p.s.

Partners

Prague Castle Administration, Goethe-Institut Prague

Dates

15. May - 10. June 2002

Place

Prague Castle courtyards and the Teresian Wing in the Old Royal Palace

Curators

Keiko Sei, independent curator of contemporary art, Ludvík Hlaváček, director, CCA-Prague

Organization

Duňa Panenková, Director, Prague Castle exhibition department, Monika Štěpánová, Goethe-Institut Prague

Production

Monika Gryčová, Prague Castle exhibition department Katherine Kastner, CCA Prague, Tamara Moyzes

Architect

Petr Hornek

Graphic design

Missing Element

Printer

Regleta

Technical assistance

Pavel Břach